Protect and empower your Creative Commons work by labeling it properly

Creative Commons is a free licensing scheme that is for copyrighted works more or less what Open Source is for software. With Creative Commons, publishers, from bloggers to The New York Times, can use and redistribute works at no cost. The license (six out of seven versions of it, anyway) merely requires that the user meet some requirements, chief among which is to properly attribute the work to its author. “Attribution” sounds like “metadata”. Let’s look into this.

When someone generously releases a work under a Creative Commons license, they are not giving their work away (generally, we’ll look at the exception in a minute). The author retains his or her copyright to the work, but grants a license allowing the user to user the work and pass it on.

If I sell you a license to a photo for one-time use for a certain amount of money, you must follow the terms of the license: use the photo once, in the prescribed manner, and pay me the money.

If I release a photo under a Creative Commons license, you can use the photo – following the terms of the license – and pass it on to the next person to do the same. That person can pass the picture on to yet another person and so on, more or less forever.

It’s a good idea

“Creative Commons helps you legally share your knowledge and creativity to build a more equitable, accessible, and innovative world,” Creative Commons says on its website. That sounds pretty altruistic. And it is. People and organizations who release work under Creative Commons licenses are contributing to our culture and base of knowledge for the future. “In this post, we’ll talk mostly about the considerations and decisions that must be made to get ready for labeling our works under Creative Commons. Once you have a plan in place and some templates made, the actual workflow process is quick and easy”

Wikipedia is licensed under Creative Commons, as are countless photos by artists with do-gooder instincts and many “commercial” works, such as most of Adobe’s support documentation.

(And that one “different” CC license? There are seven Creative Commons licenses. Six work as I’ve described above. The seventh is designed to emulate releasing a work into the public domain. Works released under that one (CC0) can be treated as they would be if they were in the public domain.)

That all sounds great, but if you’ve been reading this blog for long, you know that I wouldn’t be writing this if there wasn’t a problem that needs solving, and that metadata has something to do with the solution. So there will be a HOW-TO on the way.

We have a problem

If the requirement for using a work is that we must properly attribute (credit) the work, that implies that we must know to whom to credit it. And if we are contributing our work to the culture, that certainly implies, in the case of a photograph, that we must contribute a proper caption with the work.

A hundred years from now, a photo of some guy in a hoodie won’t mean much. But if we know the photo depicts Mark Zuckerberg at the exact moment the republic tipped toward destruction, then that photo takes on a different cultural and historical dimension.

A hundred years or a hundred days from now, an honest person can use or share a Creative Commons work in the spirit it was intended only if they know that, indeed, what they are looking at is Creative Commons, and under which Creative Commons license. If the image is somewhere other than on a Creative Commons-compliant website, knowing that is far from certain.

No problem. That’s what metadata does. We have captions and bylines and copyright fields for that sort of thing, right?

Right.

Creative Commons works critically depend on metadata

But.

They don’t have any.

If you go to the most prolific distributors of Creative Commons-licensed photos, Flickr and Wikimedia Commons, and download two or three hundred photos, you’ll be lucky to find a caption or byline or copyright notice on one or two.

That’s nuts. Crazytown.

So why are these generous, culturally-minded people not labeling their work with the very information that can ensure its long-term validity, that can make Creative Commons licensing work? Given the kind of people who inhabit the Commons, I think we can pretty much rule out selfishness or laziness. They’re just not that kind of folks.

We haven’t gotten the word out. That’s the long and short of it.

View the video version of this post

We can fix that

Stand by for the HOW-TO.

In this post, we’ll talk mostly about the considerations and decisions that must be made to get ready for labeling our works under Creative Commons. Once you have a plan in place and some templates made, the actual workflow process is quick and easy. You’ll use the software of your choice to batch apply your template and then fill in part of the caption and maybe a couple more details for each picture. The mechanics of using various software are covered in separate HOW-TO posts and videos found on this blog.

This post is, therefore, a bit like the “considerations before you keyword” post of a while ago. Like that one it’s probably going to be pretty long. Grab a cup of coffee and settle in.

Step one

Find another Creative Commoner. Grasp him or her firmly (don’t shake) and explain how critically important it is label work and communicate with the future.

Step two

Let’s see how we can do this labeling stuff.

If you’re a Creative Commoner, chances are about 299 out of 300 that a lot/most/all of the stuff I talk about in this post is new. If I gloss over some points, I’ve probably written about them elsewhere on this blog. Try the search function. If that doesn’t help, drop me a note.

What we’re going to end up doing is to use a template and metadata editing software to apply metadata to a whole batch of pictures in one go. Then, we go back and fill in the caption and maybe a hyperlink to each image individually. That will take about a minute per photo. So, doing this won’t take anywhere near as much effort as thinking about it and getting ready. I’ve broken out discussion of the “original” work, how we host it and we link to it, in a companion post here.

There are HOW-TO posts on this site that cover the mechanics of operating software. But first, we will need to consider options, make a plan, and create that all-important template.

(Later in the post, I will provide links to Creative-Commons-ready starter templates that you can easily customize for your own needs.)

Tools…

You’ll need software that can write IPTC metadata to your files. On this blog, I cover five popular graphics programs that can – Photo Mechanic, XnView, and the Adobe suite. (There are links to some HOW-TOs further down.) None of these programs is Open Source, I’m afraid. We’ll talk about that later.

For a survey of how (and how well) some programs handle metadata, see this post.

We’ll need to define what sort of information we are going to communicate and how best to do that. It’s actually the same thought process whether we are using Creative Commons or a commercial, “all rights reserved” sort of license.

When you look at your metadata editing software, you’ll see a bunch of fields, into which we’ll put data to describe our work. The fields you’re looking at are defined by the IPTC standard. The IPTC standard describes a schema. It tells us what the fields are and what kind of data goes in them.

Acronym alert! When people talk about metadata on photos, they throw around a bunch of terms. As often as not, incorrectly. It actually IS confusing. I try to be as sane about it as I can. And there’s a glossary here.

Think big picture

For our metadata we’re going to apply a strategy of communicating as clearly as possible, to the broadest audience possible, and we’ll keep an eye making our metadata as durable as possible. We want make it last as far into the future as we can.

Our IPTC metadata is carried in two data blocks within our files – IIM (sometimes, confusingly, but not actually wrongly, called “IPTC/IIM”) and XMP. The core fields are duplicated in each.

Then, there are extended fields that appear only in the XMP. There are even some special-for-Creative Commons XMP fields. (Although virtually no software can actually read them.) We will plan our strategy with all this mind. We’ll make sure our core information is first in the IIM – and especially in the caption, which may be the only field a user sees – and then we’ll populate fields that only appear in the XMP to future-proof our work.

The most important bit

Let’s start with that caption. A good caption communicates what is depicted in a photo. We need that. A good caption includes a byline – that’s the attribution we need. When someone publishes a picture, they usually publish it with a caption. Often, the very caption we provide them, word for word.

The caption is the piece of metadata most likely to seen by user/publishers. Most operating systems will display captions in their properties dialogs (although not reliably in Windows). Most halfway competent photo browsing software will at least display captions. WordPress and many other web CMSes, including every professional publishing system I have ever used, will automatically place captions with their pictures on the page, assuming that the picture has a caption, of course.

If I place a picture that has a caption in this post, in WordPress, I’ll see something like this automatically:

A quick edit and we get:

If we communicate everything that we really, seriously, need to communicate about our picture in the caption, we’ll be good.

Caption complications

But it’s not that simple. There are competing goals for our caption. It’s got to be comprehensive, yes, but it has to be publishable, just as we write it. Many publishers are just going to use the information we give them, verbatim. Some are going to let automated systems place the caption. And what we present must be palatable to over-worked editors and designers.

So, the caption may be our only shot at getting the message across, including attribution and licensing details on the one hand, and it needs to be concise, tidy and professional-looking on the other. We must balance competing interests here. But we do have other fields to help us.

The first part of the caption is the, well, caption part. Here, we have to tell the future world what’s going on in the image.

The most standard form of a caption begins with a sentence in present tense, active voice, that states who or what is in the picture and what is going on. Then one or more subsequent sentences, in whatever tense makes sense, provide background and context. (This, by the way, is AP Style, the most commonly accepted standard for such things.) For Creative Commons, we have the same goals as the AP does, and more, given that a CC work is meant to be usable in the distant future. And we have to communicate about the license.

Our caption needs a byline, too. Usually this is in a form like, “Photo by Joe Photographer/Some Organization.”

Attribution!

For Creative Commons, we’ll need to be a little, ahem, creative here. In our byline, we want to provide for would-be publishers attribution that meets the requirements of the Creative Commons license, which means we need to state the photographer’s name (OK. We’ve got that.), the license used (Getting trickier. There are six to choose from, remember.), a URL for the authoritative version of the file (How the heck are we going to do that?), and on top of all that, we should, if we can, include a link to the license itself. (Good heavens.)

From the sound of it, we’re well on our way to a monster credit line that will likely be ignored or butchered beyond recognition. So, it’s in our own interest to be as succinct and kind as we can be toward our soon-to-be publishers.

Fortunately, we have a little wiggle room. Creative Commons states that “…the manner of attribution is explicitly allowed to be reasonable to the means, medium, and context of how one shares a work.”

“…Reasonable to the means, medium, and context” basically boils down to: The publisher will give us what they can give us and that’s usually about a half dozen words. We might or might not get a link. And maybe, maybe, we get two.

The reality for someone working in publishing, whether print or digital, is that they have a standard style for credits that they have to use. A credit line shouldn’t be too long, and link functionality, which is out of the question in print, can’t be taken for granted on the web, either.

So, let’s see what we can do

What did I do? Well, the caption itself is in the style of some imaginary news wire service. It’s not great literature, but it gets the job done. Then where we would expect to find the name of Suzy’s employer, I used the space to state the license as succinctly as I could. So far, not bad.

This caption style would work for most documentary or general purpose situations. Your mileage may vary. If you do fine art, or stock photography, your caption might look quite different.

I advise everybody to write their captions in complete sentences, as they would normally speak or write. This accomplishes a couple things.

First, our captions are likely to be published just as we write them. So, we want to do a good, professional job. If we are working on a fine art image, we might end up looking at a gallery card that’s keystroke for keystroke what we wrote in our caption.

The second reason for writing captions in complete thoughts is to help when humans (including us) search for our images. The best way to have our captions match peoples’ search terms is to write them the way people think. As AI makes search engines better at semantic and natural language searches, it behooves us to give the newfangled machines as much to work with as we can, as well.

Hyperlinks?

What about the links? Those aren’t going to be elegant.

What we really want on the page is something like this:

(Right-click on the image and choose “Copy Link Address”, then go here and paste in the address to see all the metadata on the picture.)

We face a huge temptation here. We could simply put the A-tags for the links right in the caption, like so:

....Photo: <a href="https://www.carlseibert.com/commons/" rel="">Suzy Photographer</a>/<a href="https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/">Creative Commons BY SA 4</a>

We could. And it could work. Sometimes. Except when it doesn’t. And when it doesn’t, best case, we have an unprofessional-looking mess of code on the page, and worst case, we crash the end user’s system. Been there. Done it. You don’t want to.

I have seen hyperlinks in metadata. But really, it’s not a good practice. Don’t put links in metadata, no matter how much easier it would make life.

And that link to the license that we would like? Nice to have. Not life threatening if we don’t get it. If we Google “Creative Commons BY SA 4”, the first return takes us straight to the license. Not as nice as a link, but it gets the job done.

We have a lot to think about around the link back to the authoritative copy of the work. I’ve broken out discussion of the “original” work, how we host it and we link to it, in a companion post here.

Close to our goal

That leaves us with something like:

Or maybe …. “Visit https://mysite.com/commonsphotos for original file”. On the one hand, that’s not so obviously a note to the publisher. On the other, we’re depending on the publisher to figure out – by reading our Special Instructions fields, maybe – that we’d really rather have links from the credit line.

We’re dealing with the conflicting goals for our caption as best we can. Everybody understands that anything that really must be seen has got to be in the caption. So, providers often put notes to publishers or end users in the caption. There’s no absolute right or wrong here.

The thing to remember is that we must make our words sweet because we will one day have to eat them. Somebody is going to publish that caption with our note just as we wrote it. If we keep it tidy and professional, while not ideal, that won’t be the worst thing to happen in our lives. Keep it simple.

What can go wrong, will

Check out this example. I found this on a TV station’s website. 55 words of caption and 135 words of notes.

See what I mean. Somehow, this photo ran with the wire service’s correction and kill notice still bolted to its caption. Could be embarrassing. Not fatal, fortunately. (It is interesting that right in the correction, it asks the publisher to clean up the untidiness. Just because we ask doesn’t mean it will happen….)

Standards! Standards, I say!

In the ‘caption’ part of the caption, there are some standards we have to meet.

First off, tell the truth. Don’t ever misrepresent anything. That’s obvious, but it goes double for Creatives Commons.

Don’t assume. Don’t try to be omniscient.

Imagine a picture of a person in a cap and gown, holding a photo. If the graduate told you that when she looked at the photo, she was thinking of how proud her recently passed-away parents would have been, say that. Say she told you so. By quoting her, maybe. If she didn’t explicitly tell you, she’s just looking at a photo of her parents. No more.

Characterizing something as a ”scuffle” might be pretty safe. But calling it a “fistfight”, or a “donnybrook” might be assuming too much or editorializing. Is it a “breathtaking” sunset? Your viewers can see the picture. Let them decide.

Fess up

If there is anything we need to know about an image in terms of its provenance, or if it has been retouched or composited or manipulated in any way, you MUST say so. This is normal professional or artistic ethics, but it’s also a Creative Commons requirement.

In past versions of the Creative Commons licenses, the license explicitly required transparency about any manipulation that was done to the work. As well it should, especially considering that some of the CC licenses are specifically designed to allow derivative works. …make sure your own website does the neighborly thing and preserves the metadata on photos you publish. Then speak to other website owners. Encourage them to do the same.

The current version (V4, as I write) also requires you to state if the work has NOT been manipulated.

That might fly in the caption for a fine art photo, but for a documentary sort of photo, it fails the “reasonable to the means, medium, and context” test. Publishers assume their reputation and track record establishes that they’re not lying. They don’t say so in every paragraph.

There’s no better way to say “I’m lying” than to say you’re not every time you open your mouth. So, “has NOT been manipulated” just isn’t going to fly.

If you’re a strict Creative Commons constructionist, you can always put a “This image has not been manipulated” statement in the Special Instructions field.

About time

You’ll notice I put a time element in the caption. That’s very “wire service” but it serves a Creative Commons purpose. There’s no telling if the value in the Date Created metadata field will survive a hundred years from now. Putting the time element in the caption increases the chances that residents of the future will be able to know when Mann bit Dawg. Remember, the caption may be our only shot at communicating with future users. We need to make it count.

That link to the original file

We’re asking for – and, indeed the Creative Commons license requires “if reasonable” – a link to the original file. Exactly what that file needs to be, where it should be posted, and the mechanics of linking to it, are all things we need to sort out before we can properly prepare our Creative Commons photos. It’s kind of complicated. See this companion post for a discussion of factors we will need to consider.

More fields

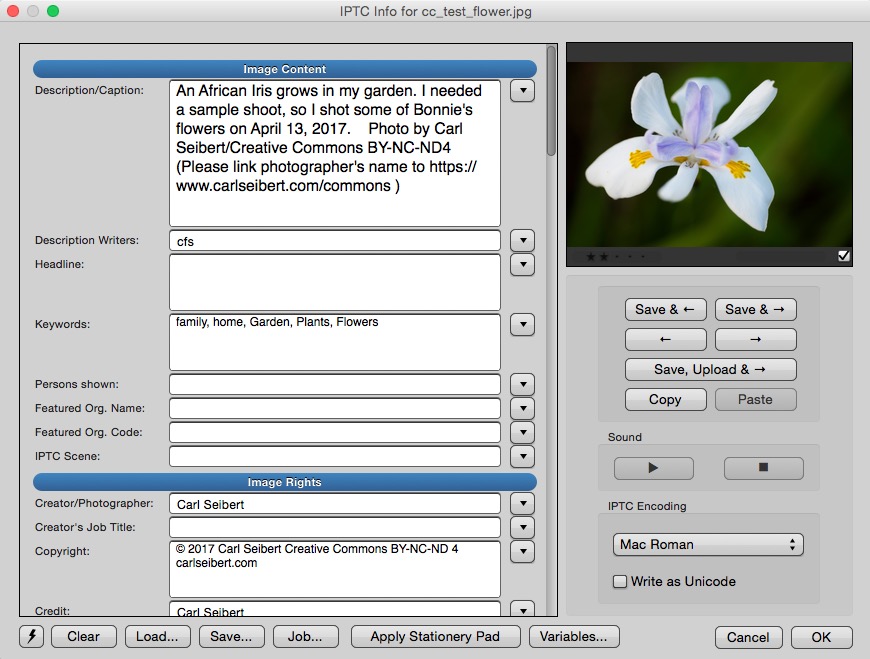

So now we’ve put a lot of thought into our caption and attribution. What about the rest of the IPTC fields?

For the most part, we can handle the rest of the fields in our metadata template. If we do them carefully once, we won’t have to worry about them again. Apart from making sure we choose the correct template for each job, of course.

Special Instructions

This field is historically used for embargoes, so we’re right in its wheelhouse if we use it explain our license terms. We can say things like:

“You may use this image free of charge for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit in a way that includes the photographer’s name and the Creative Commons license under which the image is licensed. (Creative Commons BY NC 4). If possible please include a link to the original work at https://mysite.com/mypictures A link to the license itself at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ would also be appreciated.”

(Notice that I used some extra spaces instead of line breaks or paragraph marks. Try to avoid line breaks in metadata if you can.)

I’m not aware of any publishing systems that expose Special Instructions to end users, so we can explain ourselves without worrying about our verbiage ending up on somebody’s front page.

Special Instructions, like fields that deal with contact information and the like can usually go straight into our template.

Creator and Creditline

Best practice is for Creator to be the photographer’s name – just the name – and Creditline should be the photographer’s organization, or in our case, that could be the attribution part of the inline byline from our caption.

Many publishing systems expect these fields to be used in this manner and create a byline from the values in them, like “photographer-name-from-Creator-slash-organization-from-Creditline”, or “Joe Photographer/Creative Commons BY NC 4”

Some people put the entire string they’d like to see as their credit in the Creditline field. This is bad practice from a data standpoint (disparate data points in the same field) and can lead to ugliness like “Joe Photographer/Joe Photographer/Creative Commons BY NC 4”. The IPTC now allows this sloppy use of the Creditline field. I don’t think they should.

Copyright

This field holds a copyright notice (no kiddin’). We can expand that to something like “Copyright 2018 Joe Photographer Licensed under Creative Commons BY NC 4”

Go for broke. Add “joephotograher.com” if you want.

It’s a good idea to start with “Copyright” or the © symbol, a date and your name. But there’s no set format required. You won’t “break” your copyright notice for legal purposes by deviating a bit from traditional style, or by adding brief license or contact information.

Copyright goes in the template. No worries. Do remember to increment the year each New Years Day. (Some programs, inlcuding Photo Mechanic, will do this for you, by the way.)

Now we have some fields in our core group that we will/might need to do separately for each picture.

Keywords

Keywords aren’t really intended to be public-facing. For Creative Commons purposes, we can usually safely ignore them. Keywords are terms that might not appear in the caption but might be used by someone searching for an image. (Usually. There are exceptions.) Keywords, if applied, are usually applied to groups of images. So, they’re not quite template material, but they aren’t exactly a picture-by-picture thing, either. Maybe our Creative Commons images will have keywords because we put them there to help find the pictures in our own system. That’s fine. Maybe they’ll help somebody else in the same way. It’s no biggie either way.

An exception – where keywords are as important as the caption, or more so – is stock photography. Sometimes Creative Commons photos are intended to be, basically, stock photos. In that case, comprehensive keywording might be in order. Or not. Some sites recognize keywords (Flickr) and some don’t (Wikimedia Commons). Read about keywording here.

Headline

This field can be a short (the shorter the better) headline or title for our work. We don’t need to use it at all if we don’t want to.

Older Creative Commons licenses required that users publish a title with the work. Version 4 (current as I write this) does not require one. The first sentence of our caption works fine as a title, anyway. So we’re good either way, But of you want to convey a separate title, this is a good place.

Title/Object Name

This field is often called “the slug”. It’s usually some sort of workflow code or convention that identifies the image itself or the story it accompanies. It could be another place for a title. This is another field that you can feel free to leave blank. And I actually recommend that you do that.

If we leave the Title/Object name blank, Windows users will see our Caption in their File Properties dialog and in the Windows-provided Photos application. The reason for this is too complicated (and too stupid) to go into here. But our goal is to make our caption and license information as widely available as possible. So……

Next up, XMP fields

The fields we’ve talked about so far appear in files in both the IIM data block and in the XMP data block, and therefore will be seen by users of the widest possible selection of software. (Remember we decided at the top of the post that we wanted our information to be seen by as many users as possible, and survive for as long as possible. Thus, this block stuff matters.)

Next, we have some fields that only appear in the XMP. These can be great fields, but we have to proceed on the assumption that they are icing on the metadata cake. Be sure you’ve communicated everything you really need to in the fields that show up in the IIM.

My favorite XMP-only field: Rights Usage Terms

License information goes in Rights Usage Terms. It’s perfect for Creative Commoners. Be succinct. We shouldn’t be as verbose here as we can be in Special Instructions. And remember that anybody whose software shows them Rights Usage Terms can also see Special Instructions, but not the other way around.

Contact information

In the XMP-only fields, there are ample fields for contact information, including your choice of emails, phone numbers, and URLs. By all means, use them but don’t count on them.

(There are some workflow-specific fields throughout the IPTC standard. If you need ‘em, you’ll know. For Creative Commons purposes, most of us can safely ignore them.)

PLUS

Then we have the PLUS (Picture Licensing Universal System) fields. These XMP-only fields are part of a system to convey licensing information in both human readable and machine readable form. The PLUS fields describe the content’s author, its copyright owner, and whatever license applies to the work.

PLUS does not, as far as I know, have the ability to describe Creative Commons licenses. Yet. I think there’s a tremendous opportunity for Creative Commons here. Rather than reinventing, let’s approach the PLUS organization and see if we can get Creative Commons licensing included in PLUS.

PLUS hasn’t yet achieved the traction in the marketplace that I think it deserves. But it’s got some industry backing and almost certainly has the best shot of any scheme out there now at becoming a standard way to express licensing terms.

By the way, you can register in the PLUS database of creators under your human name for free. It’s a way that potential users of pictures can find creators. I recommend registering. It couldn’t hurt.

Also on the horizon is the IPTC’s RightsML project. RightsML aims to be a machine-readable means of conveying rights information in the likes of Digital Asset Management systems. That’s where Creative Commons works could be stored for posterity. It would behoove Commoners to stay in touch with the IPTC to ensure that CC licenses can be expressed in RightsML.

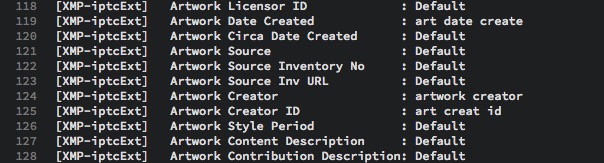

The X factor

The “X” in XMP stands for “extensible”. Absolutely anybody can create an XMP namespace. It doesn’t mean that anyone would ever see anything I write in it, but I could create my very own namespace and fields.

There is a Creative Commons XMP namespace and some fields. The open source program Exiftool, which provides backend metadata functionality for most metadata-aware graphics applications, does include support for the Creative Commons namespace. But there are hardly any user-facing programs that utilize it.

Master plugin developer Jeffrey Friedl uses one of the fields in a plugin he offers for Lightroom. But that’s it, as far as I know. The fields in the CC namespace are largely duplicative of standard IPTC fields anyway, so we have nothing to mourn here.

Chances are, neither you nor any users of your photos will ever see a Creative Commons XMP field, so we can be pretty safe ignoring them.

To learn more about the IPTC fields and how they’re used, go here and here.

Exif

There is another block of metadata in most image files that needs consideration. Exif data is mostly logging information from the camera or other device that made the image. In the Exif data, you’ll find such things as the settings used when the picture was made, details about the camera itself, and that sort of thing.

Your GPS coordinates live in the Exif data.

And there are some fields that could be interpreted as carrying copyright management information.

Normally, by the time that a picture is being readied for publication or distribution under a Creative Commons license, nobody much cares what f-stop the photographer used, and Exif data is pretty expendable. But we need to consider it. Do we keep it or trash it? What about that geotagging information?

Geotag data could be of tremendous value to a future user of our Creative Commons picture. Or, in somewhat rare cases, it could be a critical privacy or security breach. (Pro tip: If your caption includes the words “undisclosed location”, you probably don’t want geotag data on your picture.)

Camera information is often included on photo sharing sites, and if it’s available, there’s an argument for including it. It’s for the sake of history. What the heck.

To strip or not to strip

You may have already considered what to do with Exif data and made an affirmtive decision on a default choice for your day-to-day work. You may choose to treat Creative Commons works the same way or differently, but you should pause for a moment to think about it. And be vigilent for the exceptional situation that requires a unique response.

Most photo editing programs make it easy to strip Exif data from distribution copies of your work. Many make it easy to remove GPS data while leaving camera logging data. If you need to preserve GPS data while stripping the rest of the Exif, that’s a little trickier. See this post for more on the subject.

Almost ready

Once you’ve decided what you are going to say in your own Creative Commons-ready metadata and prepare your templates, you’ll need to choose and learn software that works in your workflow. Then labeling your work to give it the best chance of becoming a valuable cultural asset is dead easy.

I should point out here that there are no open source graphics programs that I know of that provide any more than rudimentary metadata functionality. Apart from the wonderful Exiftool, which is a command line program, none of the programs I write about is open source.

If you are an open source developer working on graphics software, please get in touch. We can talk about functional requirements for metadata capability.

See these posts to learn about applying metadata in Photo Mechanic, Adobe Lightroom, and XnView. (Adobe Bridge can do metadata but I don’t yet have a post dedicated to it.)

Download a set of starter metadata templates that you can easily customize for yourself here and visit this post for information on importing templates into software.

But wait!

There’s yet another challenge!

Making sure your work is labeled properly only works as long as its metadata remains intact. Unfortunately, many (most) websites strip metadata from images. That means the chances are good that if somebody grabs one of your photos off the web, they won’t ever even know that they have a legal, ethical, option for using it. That’s a tragedy.

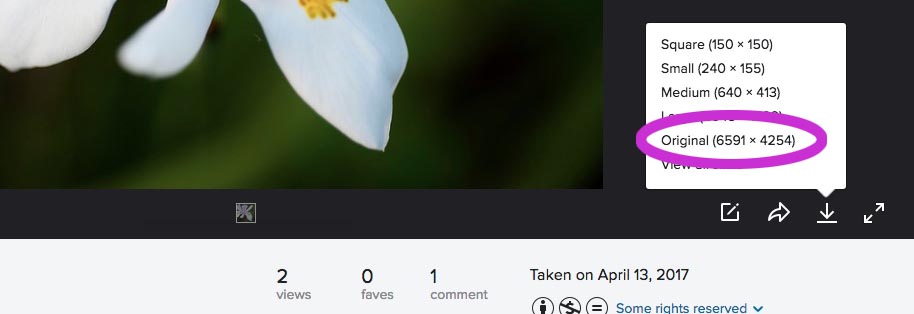

Note that Flickr only delivers metadata on the “Original” size download. Why the other sizes are even offered is beyond me, but this is dangerous. We need to be aware and we need to let people we share images with know. Read more about hosting images in this companion post.

So, step three

…is to make sure your own website does the neighborly thing and preserves the metadata on photos you publish. Then speak to other website owners. Encourage them to do the same.

Not only is it very rude to strip metadata, it’s a violation of copyright law if you do it someone’s work without their permission – Creative Commons or otherwise. Search for “Copyright Management Information” on this blog to learn more.

It’s usually an easy matter to configure a website to respect metadata. See this post and this one and this one and this one for information on doing so.

Thank you for sticking with me through this long post.

Please spread the word. Talk to Creative Common creators and publishers and archive operators who distribute Creative Commons works. Hopefully, one work at a time, we can keep Creative Commons works from becoming wandering orphans, and keep them alive for the future.

Do you have a Creative Commons experience to share? Do you have the ultimate Creative Commons photo metadata template? Reach out in the comments.