Deciding how to host Creative Commons pictures and exactly what kind of files to use requires some forethought

The Creative Commons licenses require – as long as it is “reasonable” – provision of a link back to the original work. For photographers, that means a link to an “original” file.

This is seriously important because publishing on the web degrades images big time. Just linking to where you found the photo isn’t going to get the job done.

Which means we have to figure out how we are going host and distribute that “original” file. For that matter, we need to figure out exactly what sort of file our “original” should be.

(This post is meant for Creative Commons practitioners. But any of us might need to distribute photos from time to time. Most of the considerations are the same, regardless of license type. If you’re an “all rights reserved” kind of person, please don’t feel excluded from this post.)

The license requires that link “if reasonably practicable to retain”. So, we’re talking more reasonable than the “reasonable to the means, medium, and context” requirement that applies to attribution in general. We won’t need to throw ourselves under a bullet train if we don’t get the link. That’s comforting. But we do want our future publishers to work from the best version of our work.

At odds

The way the internet works and the way Creative Commons works diametrically oppose each other. Creative Commons envisions a work traveling across time and space from one user to another, in some cases evolving as it goes. But the way digital publishing works, images are degraded upon publication and degraded more and more with every subsequent publication.

When I upload a photo to this site (which is on WordPress, but all modern CMSes work the same way), I make a version of my photo that’s the largest size I want to display on, or distribute from, my page. I use lossy compression aggressively. The CMS then takes that file and makes a series of files, each smaller than the last, and compresses them literally within an inch of their lives. Then, depending on the device a visitor uses to view my site, the smallest usable file is served. The goal is to squash the files down to the point where any further compression would render the quality of the image unacceptable.

So, except possibly for that biggest one, any photo you download from my site is almost too low in both resolution and quality to use. If you squash it again, it’s going to get worse. Much worse. And if the next person does the same…. you get the idea.

View the video version of this post

A vital link

So, the link back to the original becomes pretty important. Without access to a clean high-resolution file, our picture will die in a couple of generations, metadata or no.

We have to face some tough considerations about that link. For one thing, we know that it can’t be a zillion characters long. That would make a mess of our caption. Link shorteners aren’t a great option either. Many sites don’t allow them. And will Bit.ly be around fifty years from now? Will my site be around then? Will yours?

Hmm. So, we need archivally sound repositories and reasonable links to them. That’s a tall order.

If your photo is included in the curated collection of an established library, that’s great. For the rest of us, the options come down to self-hosting the image or Flickr (or someplace similar, professional portfolio sites like Zenfolio and Photo Shelter pop to mind) and hoping that the image will eventually find its way to someplace stable, like Wikimedia Commons. Or maybe, the image could live in several of those places. That would give it the best chance of survival.

Flickr

Flickr says it is the largest repository of Creative Commons images. Most of us who use Flickr, regardless of for what, have a love-hate relationship with the site. Well, OK, make that a hate-hate relationship. Or maybe a we’re-just-dating-but-we-don’t-really-like-each-other kind of relationship.

The interface is obscure, to be charitable.The site’s support for metadata is confusing and spotty, and the URLs for photos are long-ish.

The site is owned by Yahoo!/Verizon/Oath/and now SmugMug. That doesn’t inspire long-term confidence on the archival front. SmugMug announced their purchase of Flickr mere hours ago, as I type this. Will they be an improvement over the busload of clowns before them? Will Flickr last in their care? Only time will tell.

On the upside, Flickr is where a lot of content is. The search engine works pretty well (if photographers do a decent job with metadata, that is) And Flickr has good Creative Commons support.

When you upload a photo to Flickr, Flickr will import and contents of your caption field and map it to its own (searchable) caption. That’s a win. You don’t have to retype.

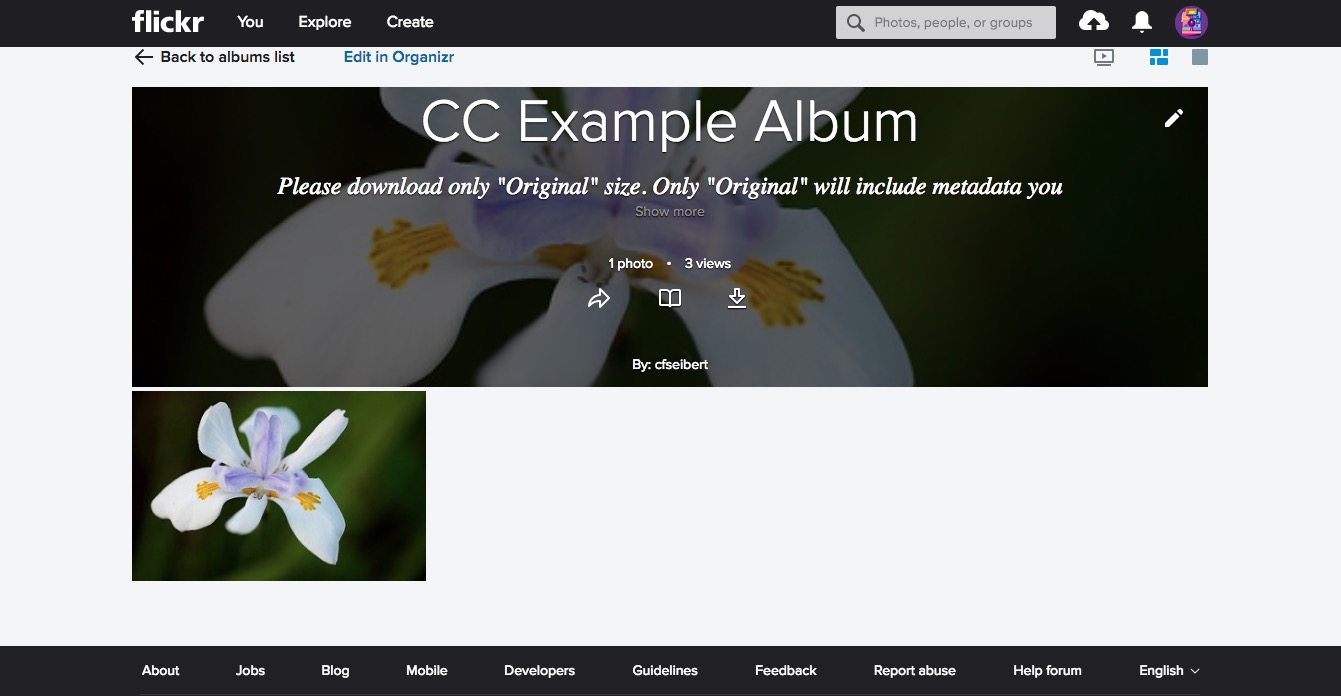

But Flickr only includes your metadata on the “Original” size download. Harumph!

A bit of good news on that front: Flickr automatically makes sure that “original” downloads are enabled when you choose a Creative Commons license. A bit of bad news: You’ll need to tell prospective users that, because trust me, they won’t have a clue. That means typing or pasting a note somewhere on the photo’s page, which is more work. And it might not work.

Hint:

You can post a comment under your own picture with that information. There’s no guarantee that prospective users will see it, but this seems the easiest way.

Flickr URLs aren’t exactly svelte, but they’re not too outrageous (usually).

Flickr content is indexed by Google Images, or at least Flickr claims so.

And Flickr Creative Commons content often finds its way into the curated Wikimedia Commons collection. That’s a good thing.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons hosts a large collection of Creative Commons and public domain works. If your work meets the standards for inclusion in the collection, this would be a great place for the authoritative copy of your work to live. See the guidelines for submitting work here and here and here.

It appears that Wikimedia Commons, like Flickr, only honors metadata on the “Full Resolution” version of a downloadable photo. That’s not especially good. Most rational downloaders will opt for the biggest version of the file offered. But anyone who downloads a smaller version won’t receive any metadata.

And, if you are infringed and the copyright management information is stripped from the image, there could be difficulties establishing that the infringer did it on purpose. Please join me in encouraging Wikimedia Commons to properly preserve metadata on all photos they offer for download.

Hosting your own work

You can link back to somewhere on your own site.

On the positive side, if you host your own authoritative copy of your work, you have control. You can easily keep the URL sane. If it matters to you that people will visit your site, there’s that.

You could make a special page for your CC work, or, depending on your web CMS’s capabilities, simply make a high-resolution version of your image available right on the page where you published it.

Visitors to most sites expect that if they click on an image, they will be taken to a large version of that image. It’s usually about 2,000 pixels wide. But there’s no reason you can’t make it be the full-res 6,000 pixel file. (As long as you make sure you don’t try to serve that giant file on the page, of course.) You could help by pointing such a thing out with a note in the caption – the one on the page, not the one in the file.

On WordPress, for example, the CMS makes a series of files of your image in decreasing sizes. The first in the series is called “original”. It is, in fact, the file you uploaded to your server, untouched by the CMS. It can be as big and of as high quality as your server can handle. You could use it to distribute your Creative Commons licensed image.

On the downside, there’s the expense of hosting large files. And will your site be available fifty years from now? Not likely. Will it be available longer than Flickr? Hmmm.

Make (your own) work as easy as possible

The link back to your work can be a fiddly pain in the neck if it has to be unique for every picture. It’s probably going to end up being that way for your eventual publishers. But hey, they’re getting use of your work for free. You, on the other hand, have a tee time waiting. (Or whatever) Can you avoid messing with that darned link on every picture you license under Creative Commons?

Quite often, yes. Consider the possibility of hosting multiple pictures under one URL. Make a landing page on your site. Park your Creative Commons images on it. And build the URL into your templates. What’s more, the URL is likely to be something nice and friendly, like “carlseibert.com/commons”. If you have a lot of images on your landing page, would-be users of your pictures will have to browse a bit to find the right one. But as long as you keep it reasonable, that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

If you use Flickr or a similar service, you may be able to accomplish the same thing by using an album. Like, so https://www.flickr.com/photos/carlseibert/albums/72157689306963580 Now you can put the address of the link right in your template.

About that file

Then, there’s the matter of what the “authoritative file” should be. There isn’t a lot of meaningful guidance at Creative Commons on the matter. We’ll use our common sense superpower to work this out.

As a piece of visual content goes through its lifecycle, it will morph through a number of iterations. At “birth”, our content (a photo, we’re assuming) will be a file written by a camera. It might be a camera RAW file, or it might be already processed and saved in some sort of standard format, usually JPEG.

Next, we work on that file and produce an edited version, with color and tonal adjustments, cropping, and perhaps even retouching or compositing, if that’s appropriate for the type of work we are producing. This “final” version of the work is usually saved in some sort of lossless format, like TIFF or PSD. There are no official names for these stages in a work’s life. We’ll call this one the “master”.

(In some workflows – Adobe Lightroom is an example – the “master” is only an XML file or a database entry describing the editing steps used to create it from the original camera file. This accomplishes the same objective.)

For distribution

Next, if the picture is to be distributed or published, a new version is prepared from the “master”. This time, extraneous metadata that’s no longer needed (Exif, most likely) will often be stripped away and perhaps a new set of IPTC metadata will be applied. This new version is saved in a format suitable for transmission to publishers or archive sites.

Nine times out of ten, that works out to be a full resolution JPEG with minimal compression applied. Sometimes pixel dimensions are reduced to meet a publisher’s specification. And sometimes the format will be TIFF, or rarely, PNG. For lack of official nomenclature, we’ll call this version the “distribution master”.

The “distribution master” is replicated and sent to publishers, where new versions are produced. Websites will make smaller, severely compressed images to serve on their pages.

So, an image that went out into the world as a glorious 6,000-pixel wide file with full tonality and brilliant color (and a Creative Commons license) finds its way to your computer as a bedraggled-looking, squashed low-res with fuzzy details and scaly-looking colors. (And hopefully, by hook or by crook, its Creative Commons license information still intact.)

All was well until that last step. That all suggests that what we should point our link in the attribution to should be the “distribution master”.

Up to you

What characteristics, exactly, that version should possess is up to you, of course.

Do you want to distribute your final interpretation of the image or something “unedited” and closer to the camera original? Your carefully chosen colors and tones, or a “flat” version that others might interpret in their own way? In an easily distributed, traditionally accepted lossy file format (JPEG), or a bandwidth-eating lossless archival format? Or maybe in a new whiz-bang format (FLIF, HEIF, WEBP) that might not be around years from now? These are all choices you will need to consider.

For what it’s worth, the full resolution, minimally compressed JPEG is something of a defacto standard. It’s easy to handle, is usable by nearly every piece of software on the planet, carries metadata both in the IIM format that is in near-universal use today as well as the XMP format that is its heir apparent. It is highly likely that JPEGs will be around and usable in the distant future. And Creative Commons considers the format an acceptable “open” format.

(A few years ago, many people, the Creative Commons organization among them, thought that the change from IIM metadata to XMP was imminent. It hasn’t happened. As I write this, virtually all metadata reading software reads IIM, and relatively few programs can understand XMP. This argues against using PNG as an authoritative file format. In addition to its clumsy file sizes, PNGs can only carry XMP metadata. XMP is the future. Or will be someday. We can’t ignore it. But, for now, we have to work with what we’ve got. )

Linking back to your Creative Commons (or other) images is yet another matter where, if you think it all through ahead of time, and proactively make some arrangements, the actual doing of the thing can be practically effortless. (Just including a standing link on your Creative Commons metadata template might be all it takes.)

Have you built a better mousetrap? Dive into the comments and tell us how you handle distributing high-res files.