Before you start keywording, you need to consider stuff and make a plan

What are keywords? Why do you want them? Why is there air? Keywording is probably the trickiest wicket in the whole metadata game. Your keywording regime requires more forethought than most any other component of your workflow.

A good keywording approach depends heavily on a specific understanding of your collection, your searching needs, and the capabilities of your archive system.

There are lots of shades of gray here. Keywording can be controversial. While there is consensus on many points, if you want to see an …er, lively… discussion, get a half dozen librarians in a bar and bring up keywording. Bonus points if somebody throws a beer mug.

And yet everybody seems to want to keyword. Profusely and badly, usually. Look at the How-To videos on YouTube. There are dozens. Best I can tell, most photographers think that lackadaisical keywording is all there is to labeling their photos. So, many of us are wrong-footed before we even start. Thus, this post…stuff to think about before you dive in.

What are keywords?

Keywords are bits of metadata that characterize and categorize images in ways that captions don’t.

Captions – and most of the metadata we add to photos, for that matter – communicate information to other people, or maybe to you, sometime in the future. Information like who or what is depicted in the photo? Who shot it or owns it? Where and when was it made?

Keywords are just for us.

They help us find stuff. Other people will rarely even see them. Technically, the kind of keywords we’re talking about are comma-delimited lists of terms that we put in the IPTC Keywords field and that will return a given photo if one of those terms is used later as a search term.

Wait. What?

Three key concepts in that last paragraph bear examination.

1. Keywords go in the IPTC Keywords field. Competent software will put them exactly there. It isn’t brain surgery. The key word here is “competent”. (Sorry about the pun) Everybody and his dog has written a photo management program. Many of them suck. If a photo management program puts your keywords anywhere other than the industry standard field, that means you will lose the keywords when you change software. Which you will do. Sooner more likely than later. Don’t use software that doesn’t write your data where the standards expect it.

(Note that a lot of software separates keywording and captioning into two different parts of the interface, usually to bad effect, UI-wise, but they do it. That doesn’t mean that the program isn’t writing where it should. It means you need to check carefully.)

2. Keywords can’t be depended upon to represent what’s in the image. If, for an obvious example, you are a stock photographer, you want your photo to show up in as many searches as possible. You may add keywords that are synonyms, or are conceptual, or may not be the correct names of things that are actually in the photo, like “Xerox” because that’s what people think when they think copier, regardless of what brand of copier is really in the picture. (The Xerox thing is just an example, by the way. Don’t do it!)

We can’t trust keywords to tell us what’s depicted. They’re only there to help us find stuff. What’s depicted is the caption’s business. If you have a picture of a certain genus of mosquito, say so in the caption. Users need to know for sure. Just because your picture came up in a search for “Haemagogus”, that’s not the same thing as assuring users that this is the real deal, not some off-brand mosquito.

Captions are mandatory. Keywords are optional. (Which you may remember as “Landings are mandatory. Takeoffs are optional”, if you’ve been around aviation.)

3. Keywords and search terms are not the same thing. Not for us, anyway. Search terms are words you enter to find stuff. Keywords are special words that live in the IPTC Keyword field.

People talk about “keyword searching” in a very general way. We have to be specific when we speak of keywords and keywording, or we’ll go crazy.

“Tags”, by the way, are generally keywords in “our” sense of the word. “Tags” sounds younger and cooler, and it takes less space. It’s a nice word. Life would be simpler if could just use it instead. Oh well.

So is every sentence about this subject going to require eight paragraphs of explanation? Will I be writing all night?

It’s already sounding complicated and uncertain

Are you fidgeting around, waiting for me to say that you can live your whole life happily without keywords?

You can live your whole life without keywords. There!

But you probably don’t want to.

Now, If you’re still with, me, get a cup of coffee and settle in. We have a lot to talk about. Altogether, this post is about a twenty-minute read.

Here’s the plan for this post:

I’m going to present a bunch of points that need to be considered before you build a good keywording strategy. Then, with that information well digested, you can make a simple plan that will work for you. Keywording should take a few seconds, and for batches of pictures at that. Think over the complicated stuff in advance, make some simplifying assumptions, and go forward.

Before you lay finger to key to keyword your first picture, carefully consider the content of your pictures and how the people you anticipate to be users will likely search for them. Plan your keywords accordingly.

When you’re actually applying keywords, don’t overthink or overdo. Keywords are just helpers. They don’t (usually) carry the whole burden finding your work. You don’t need them to be perfect.

We’ll talk about the actual mechanics of using various applications to keyword your photos in future How-To posts.

When I worked for a newspaper, we had over two million photos in our collection. We basically didn’t use keywords in our searches. And we were deadly accurate in our searching.

Frankly, we should have made better use of keywords. But we didn’t perish from doing without.

Captions vs keywords

I always tell people that when they write their captions, they should describe what’s going on in the picture clearly and accurately. They should assume that someday, somewhere, somebody is going to publish that picture with that caption, exactly as written. So, it should be written in complete sentences, in proper(-ish) grammar.

But there’s another reason. I tell you to do it that way because if you tell the story naturally, you will automatically include search terms that people will naturally think of. When they look for your picture, they’ll likely come up with search terms that match what you have written.

The better the search engine in the system that searcher uses, the more likely that it, too, will think about language as it’s naturally used. Consider how wonderfully Google understands natural language queries nowadays. Photo management and Digital Asset Management systems don’t use search technology as good as Google’s, but they’re getting better all the time.

And users, unless they spent the last twenty years adrift on a raft with a big tiger, have become pretty skilled at choosing natural language search terms. Searching against captions is a natural, powerful thing. If all your pictures have good captions, keywords become pretty optional.

Google, by the way, doesn’t use meta tag keywords (the equivalent of our IPTC keywords) anymore. That tells us something.

What should you use keywords for?

Keywords are useful as descriptors that can’t go in the caption. If you’re doing a clothing catalog, the SKU number of the item in the picture might be a handy tool for in-house searching. But you probably don’t want to put such a thing in the caption for the whole world to see. Make it a keyword.

If you are marking up sports pictures, it might be awkward to put the name of the sport in every caption. Or you might just forget every now and then. Keywords to the rescue.

Many websites use filter-based navigation. You click on “clothing” and then “men’s” and then “shirts” and then “pullover” and so forth. Those terms are keyword fodder.

Keywords are great for categorizing. I used to often need to call up a picture of a football, to silhouette for an icon. “Football”, depending on the season, would return 50,000 to 100,000 pictures from our system. A half dozen of which of were actually pictures of footballs. We could have made great use of some keywords like “product shot”, or “on-white”.

Keywords that could, for example, be used to sort out the catalog pictures of the Mark II Widget from action shots of its production line, or from portraits of its designers, might be worth their weight in person-hours.

Keywords are good at describing concepts, like “love”, “family”, or “happiness”. You wouldn’t want to – or in most cases be ethically allowed to – make judgments about the mental state of your subjects in the caption. But one day, you may need to find pictures that show, say, “teamwork”.

Synonyms as keywords

Keywords can be synonyms that people might use in a search, but that wouldn’t fit properly in a caption. “Bike” could stand for “motorcycle” or “bicycle”. Only one will likely fit in the caption, so you might add the other as a keyword.

But be careful! Be aware of your context before you add synonyms. Let’s say you have pictures of both soccer and American football in your collection. In most of the world, soccer is “football”. It would be tempting to add “football” as a keyword synonym for “soccer”. But if you did that, you would mix all your football and soccer pictures into a terrible jumble. That would be bad.

Good keywords are specific to both the contents of a collection and the system that will search for them.

First, let’s consider the context of your picture in the collection.

Let’s say you’re a sports association. For bicycling, let’s say. Now, right off the top, the keyword “bicycling” isn’t going to be very helpful. If you have a zillion pictures in your collection, “bicycling” will return, oh, a zillion of them. We can safely skip that one for our own system because nobody in your association would ever use it. They already know the collection is full of bicycling pictures.

The names of riders aren’t keyword material, either. They’re in the captions. The cities in which races take place probably shouldn’t be keywords because they appear in their own fields. But regions, like “northeast”, or “west coast” might be useful. Those terms wouldn’t appear elsewhere and could be keywords.

(I won’t say I never abuse a field by doing something like putting country or city names in keywords. I, ahem, have done that. But if you’re going to do it, you need to put in some hard thought about the potential consequences. Would your hack render some photos un-findable, or would it really and truly be OK? If there’s a conceivable way that hacking a field might lead to data loss, don’t do it!)

Think about the things that people in your bicycling association might search for – that wouldn’t already be in captions.

Sponsorship is certainly a big deal. Captions probably wouldn’t include all of a team’s sponsors. What about when the pedal sponsor wants to donate to your association and you want to find all the pictures of riders using their pedals? OK! We’ll put sponsors in keywords!

Types of races, like crits or time trials? Yup. Activities, like climbing or sprinting? Yup. Categories, like action or podium/jubilation pictures? Absolutely.

On the other hand

Some photographers mark up their work with inside-baseball keywords like “portrait” or “landscape” (meaning the dimensions of the picture, not actual portraits of people or shots of grain-covered fields) or “blurred motion” or the name of the color that dominates the scene. For somebody, somewhere, those are probably meaningful ways to categorize work. For most of us, they are secondary considerations that won’t be part of a search, and thus, are not worth the bother.

If I want a vertical picture of mostly red fall foliage, I’ll search for “fall foliage” or “fall AND (foliage OR leaves)”, if the system will let me. I can see for myself if the photo is red or not, as fast as I can scroll past the results. As for verticality, if I don’t see a vertical, I’ve got my chainsaw-like crop tool.

You get the idea. Before you lay finger to key to keyword your first picture, carefully consider the content of your pictures and how the people you anticipate to be users will likely search for them. Plan your keywords accordingly.

It’s the system

Now let’s think about the system that will search for your pictures. Probably it’s going to be software on your own computer. Or maybe you’re submitting pre-keyworded images to a stock house. You could be looking at systems with very different capabilities.

You’ll upgrade or change your system over time, and you can’t always know exactly how somebody else’s is going to work, so this part is going to be tricky.

That said, we can make some generalizations.

You will move up. However good the system that houses your 50.000 image collection today might be, it’s a pretty safe bet that the one you move up to when you have 500,000 images will be better. So, what works today will probably be even more powerful tomorrow. Probably. But there’s no guarantee that your favorite feature today will be in your next software.

Size matters

Your keywording experience could be different if you are working with a bigtime DAM system, compared with a little desktop application, like Lightroom.

For instance, I often see people knocking themselves out keywording synonyms even though their work is going into a sophisticated archive system. Good DAM systems have a built-in thesaurus function.

Thesauri are lists of synonyms. Such a system probably already knows that “bike” could mean “motorcycle”, and “Steven” means “Steve” And if the search engine is good enough, it might know from context whether “bike” means “motorcycle” or “bicycle”. In that case, hard coding synonyms would likely be a waste of your time.

Desktop systems, on the other hand, rarely have thesauri, nor do they have powerful search engines. In that case, BYO-synonyms.

Synonyms can be dangerous. Hazardous. Tricky.

Again, we have to be cautious around synonyms! They can bite!

I once knew a guy named Jorge. People often called him “George”. Rather than fight, he just went with it. People might search for him as “George”. Would I want to go in my thesaurus or structured keywords list and associate every “George” in my collection with every “Jorge”? Heck no. I have to make an accommodation for this one Jorge/George.

I would probably take care of this Jorge/George thing in keywords, not in the captions. I don’t want to clutter up my captions. And the fact that some people don’t call the man by his right name is probably not relevant to the picture, So, “George” would go behind the scenes, in the keywords.

In another case, I worked with pictures of a public figure who changed from using “Stephen” to “Steve”. That, I did handle in the caption. I wrote a brief note that explained what he had done and appended it to the caption of every picture we had of the guy. Anyone who accessed those pictures would understand what was up with the name. And search for “Steve” or “Stephen”, you’d find the guy’s pictures either way.

People often change their names when they marry. Same idea. It’s likely that you’ll want both the old and new names to hit in searches. It’s a case by case synonym affair. Solution in the Keywords or Caption? Your choice each time.

A capital idea

You may have heard advice suggesting capitalizing only proper noun keywords and making everything else lowercase. That’s good advice. Why? Well, most search systems are not case sensitive. Most desktop apps aren’t anyway.

And sophisticated systems that might be capable of case sensitivity usually have the feature turned off.

And most searchers enter search terms in lowercase.

So why make the effort to capitalize proper nouns?

Consider the professional researcher who is threading the needle between “Bush”, as in George W, and “bush”, as in rose. That researcher could turn case sensitivity on for this search and eliminate however many zillion “Bush” pictures accumulated through eight years of his presidency. In which case, capitalizing the proper name would pay off handsomely.

But not

What if our researcher wants to avoid the uppercase Bush White House altogether, including the lowercase bushes in its rose garden? If so, our professional researcher, working on a fancy professional system could deal with that by adding “NOT White House” to the search.

Yes, You can use keywords to exclude returns from a search! IF your system is capable of it.

You could, for example, apply “NSFW” as a keyword to pictures that, well, aren’t. And then use a NOT search to exclude, say, Jennifer Lawrence’s bathroom mirror selfies from the rest of Jennifer Lawrence. But wait….about that system thing…

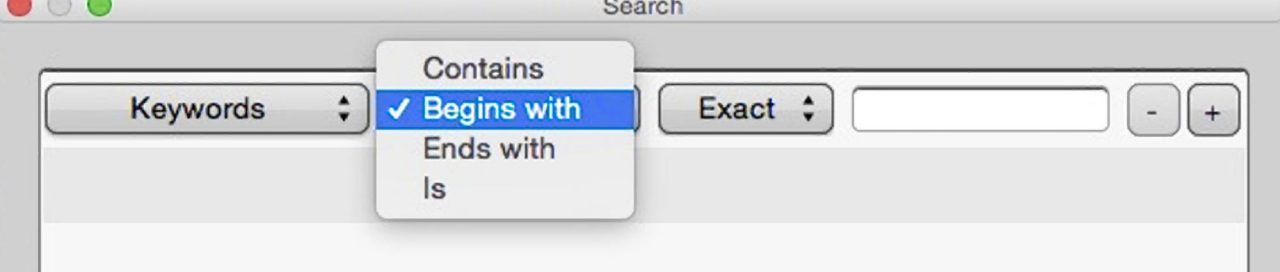

“NOT” is a Boolean operator, like “AND” and “OR”. Really sophisticated systems allow the researcher to string Booleans together and enter complicated search statements that look like algebra equations. Simpler systems, like Photo Mechanic and Lightroom, help us out by abstracting the Booleans to pulldown choices like “contains all of”, “contains any of”, or “does not contain”.

Some applications allow us to search across multiple fields, like “Caption contains Jennifer and byline is exactly Joe Photographer”. (Photo Mechanic does; Lightroom doesn’t.)

So far so good. If we can combine those two ideas and somehow do “Caption contains Jennifer and Keywords do NOT contain NSFW”, we’re golden. We get pictures of Jenny that are safe for the office.

But most desktop applications can’t do NOT searches at all (Photo Mechanic), or they can do NOT searches, but they can’t apply them to specific fields in a useful way. (Lightroom). If we were using either of those programs, we’d be NSFW-word-ed.

(Update: It turns out there is a workaround that will allow you do a NOT search in Lightroom. Look in the comments below.)

So, if your keyword strategy includes keywords for things you want to exclude from search returns, you need to find out if that’s possible with your system. If not, you’ll need an alternative plan.

More system quirks

Most of the time default searches will run against both the Caption and Keywords together, or maybe across all fields at once. Some systems allow the user to switch between fields or use independent search terms for each (like our Jennifer Lawrence search in the previous section). Check your own situation and decide if you need to make adjustments to your keywording strategy.

Plurals can be an issue(s)

Many sophisticated systems can do pluralization. They know that “car” and “cars” usually mean the same thing, search-wise. (And the top notch ones even allow the searcher to turn the feature on and off.)

Most desktop systems can’t do pluralization at all. If yours doesn’t, you might want to consider using plural/singular synonym keywords to solve the problem.

Some people advise us to use plurals for all keywords where the spelling is similar – “cars”, or “brushes”, for example. That’s generally good advice, but it’s another case where we need to know how our system will act. The idea is that some (many) systems will return “cars” if you search “car”, but not the other way around. Will yours?

If you are working with your own collection, you might want to just make a convention that says “I’ll only search by plural spellings (or vice versa). But wait. Some keywords just don’t make sense pluralized. And some don’t make sense as singulars. Do you go with “makes sense”, or do you brutally force a convention? Sigh.

So the pluralized keyword thing goes in our list of “probably good ideas that might or might not make sense in your case, but you have to make some sort of decision anyway” dilemmas.

A few or many?

Most of the time, people want keywords to help their search results zero in on just the most relevant images. Consider the “football AND product” example. We want the fifty pictures of the ball itself, not the fifty thousand of the game being played. That suggests one approach to keywording.

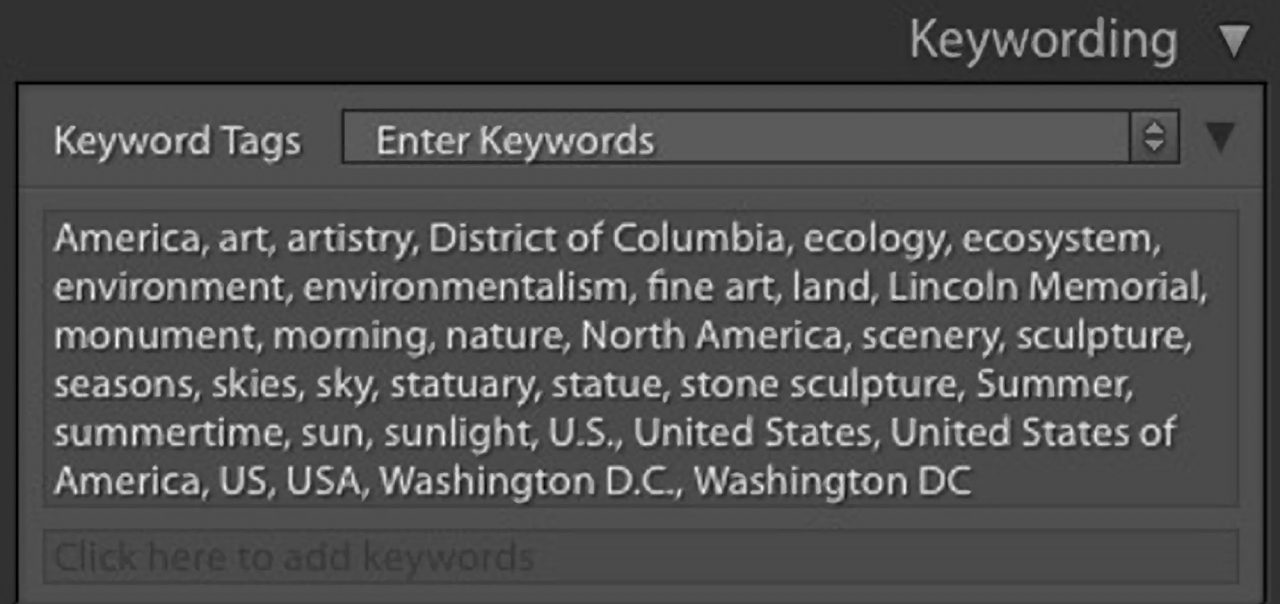

But sometimes, the goal is to make a given image return for the widest variety of searches possible. Such is the case with stock photography. You often see stock photos with an immense set of keywords and a five-word caption. (Or no caption, even.) That suggests a very different approach to keywording. Identify your own goals going in.

Control your vocabulary!

Seriously, this is a real thing, and it’s huge.

Keywords only work if they are consistent.

Look at the list of existing keywords on most any collection of pictures. It’s not going to be a pretty sight. There may be hundreds or thousands of keywords that appear on only a few pictures each. There will be misspellings, variant spellings, useless synonyms, and one-offs that just should have been in the caption instead.

My personal collection includes samples from various services and sources, some of my own professional work and a huge hodgepodge of family snapshots. I’m more of a caption guy than a keyword guy. But still, DigiKam shows me a keyword list of 483 terms. Most of those are just getting in the way.

In the “N”s, my eye fell on “nudity”, “nude”, “naked” and “NSFW” (of course it did). Now, assuming I could use those keywords to limit a return to safe-for-work images, which one would I use? (This is hypothetical. DigiKam can’t do NOT searches.) If my software would cooperate and I wanted to make that work, I would have to choose one keyword for that concept and apply it consistently across the collection.

This is why we have something called “controlled vocabulary”. “Controlled vocabulary” is a term usually used around databases. In this example, “controlled vocabulary” means limiting the possible choices for words that mean “not safe for work” to (hopefully) just one. Then tag every picture that meets that criterion with that specific keyword.

Build your (controlled) vocabulary

Having and using a controlled vocabulary makes the difference between keywords working well for you or dogs-and-cats-living-together chaos.

Make a controlled vocabulary of keywords and when you apply them to your photos, choose the right ones from the list. Don’t write them freehand or make them up as you go along. Yes, from time to time, you may need to add a word to your vocabulary. But if you possibly can, update your list, rather than one-offing one picture. Don’t wing it. Don’t type if you can help it!

(Be very careful about deleting or editing keywords in your list, by the way. Some software will alter existing information in your photos when you do that. (Lightroom, I’m lookin’ at you.) You might want this behavior or it might be disastrous. Be forewarned!)

Your controlled vocabulary should be as small as possible in the context of your collection. If you are the Library of Congress or Getty Images, it could be a long list indeed. But for most photographers, a few dozen to a couple hundred terms will probably do fine.

You probably don’t want to sit down and think up hundreds of keywords from scratch. Go through your existing keywords and choose the ones that are really useful. Or consider finding a pre-built list on the internet. I’m usually skeptical of off-the-shelf keyword lists, but you might find one that’s perfect for your needs.

“Little buckets”

As you create your vocabulary of keywords, think of your keywords as little buckets for your images. Quite a few pictures should fit in each bucket.

In most cases (the SKUs in shirt example above being an exception) you don’t want to keyword down to per-picture specifics. That’s what captions are for. If a keyword applies to fewer than a dozen or two pictures, you’re probably duplicating work that should be done in captions, and your keyword list will grow large and unwieldy.

Hint: If you are using keywords in a search, it’s often helpful to refer to your keyword vocabulary as an aid to formulating searches. Yet another reason to keep it lean.

Another hint: If you store your images in a folder hierarchy, the names of folders in your path are often good candidates for your keyword vocabulary. “/clinic/doctors/orthopedics/”, for instance. Especially be mindful of that “other” folder path a picture might fit in. If, say, the same picture might go in “/operations/orthopedic/pediatric/” That’s two more keywords to consider.

Most every point in this post, in one way or another, argues for the controlled vocabulary concept.

It’s hugely important. Write it on a 3×5 card and staple it to your forehead!

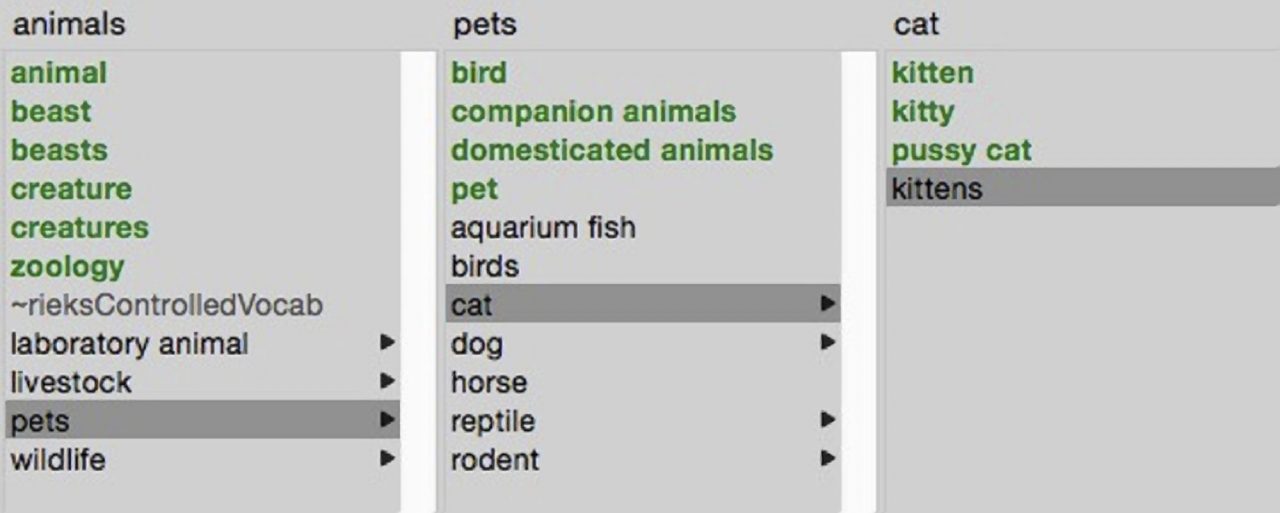

Hierarchical keywords

Closely related to controlled vocabulary is the concept of hierarchical, or “structured” keywords. Here, if the software we are using allows it, we can, at one go, assign keywords in hierarchical paths, with synonyms thrown in for good measure.

Let’s say we have an image of a classic car. The keyword “Stingray” could bring along, in one stroke, taxonomical antecedents like “Chevrolet” and “automobiles”, with synonyms like “Chevy”, “Corvette”,“cars”, and “sports cars” thrown in for good measure.

Clever software would allow you to easily choose a different taxonomy for “Stingray” as used in the context of fish.

Structured keywords also allow you organize a long keyword list into categories for easier use. That’s handy if you have a bunch of keywords.

Hierarchical keywords make it really easy to add synonyms. But don’t get carried away. Synonyms are still tricky, remember? Do you really want that Stingray picture to come back every time somebody searches for “car”? Would that help? Or would it render the search term “car” useless?

Decisions. Decisions. Make them in advance as much as possible. And go easy. Don’t overdo.

We’ll cover the mechanics of using hierarchical keywords in How-Tos for specific software in upcoming posts.

Are there situations where keywords are more important than captions?

Yes, “Captions are mandatory. Keywords are optional”, is a generalization. Like most generalizations, it’s generally true. But there are exceptions.

Consider the shirt company. They need to find shirts in a taxonomy of clothing. They probably need to fuel a filter-based navigation system for their e-commerce site. Their pictures are intended for their catalog. Few, if any, will ever be used in a place that publishes captions.

So, captions on their pictures aren’t going to be of much use to communicate with end users. Which turns the captions-first philosophy on its head.

(That said, end users cannot be expected to look at, or even be able to look at, keywords. If ShirtCo actually wants an end user, or even their own designer, to know what the SKU number of a shirt is, they’ll need to put it somewhere where such a person will see it – like the caption.)

So, for ShirtCo, keywords will carry most of the weight. They should probably put a generic caption, like “ShirtCo introduces it’s 2018 fall line.” on all the photos, just in case. But in their case, the caption plays second fiddle.

Stuffing stock

We’ve already talked about stock photos. Most stock photos aren’t real in the first place, so there’s not much to say in a caption. I often see stock photos with perfunctory captions like, “Couple watches the sunset” – or no caption at all. The couple isn’t real. They’re professional models. I have my doubts whether the sunset is real. But that photo may have a string of keywords as long as this post.

And finally, my favorite thing about keywords!

Since they’re little buckets that you can assign to batches of photos, keywords are perfect for marking up- as best you can – legacy collections of metadata-less images.

Think of my mishmash of family pictures. I couldn’t caption them all if I lived to be a hundred. Heck, I couldn’t caption them all, period. Years after the fact, I have no idea precisely what was going on in most of those pictures. But I surely can go through and select batches of images and apply keywords to sort them into those “little buckets”. I won’t be able to search for specific photos, only “little bucketfuls”. But that will have to do.

Companies trying to bring order to an unruly corporate collection face the same challenge. Hiring an archivist (or someday maybe a robot) to go back and keyword will expensive, but trying to mark up images individually with captions would be absolutely prohibitive.

One last major consideration:

Don’t try to be perfect. Don’t over “front load” your archiving workflow.

Think about, if – maybe once a month, you spend a solid hour digging around to find some particularly reclusive photo. If doing a more thorough job of keywording or captioning would mean that photo pops up instantly, that would be a good idea, right?

Well yes, but only IF doing an improved job on the front end would cost LESS than an hour per month. Otherwise, you’d be wasting time that could be put to better use making pictures or playing golf.

Put it all to use

Now you’ve been with me for twenty solid minutes and a whole cup of coffee. It’s time for the payoff. In order to put all this information to practical use, you’ll need a simplifying assumption or two.

So sit down with a notepad and another cup of coffee. Consider your collection of images and your goals. What kind of stuff do you have? Who is going to be searching through it? For what reasons? With what software?

With that and the examples I’ve laid out for you in mind, make a plan and start building a controlled keyword vocabulary. You don’t have to, nor will you be able to, build your whole vocabulary down to dotting the last “i” in one go. Make a reasonable starting point.

Now, with your starter vocabulary in hand, go forth and start keywording your pictures. At first, you’ll often find that you don’t have the right keyword. Stop and think it through and carefully add a new keyword to your vocabulary. Don’t be flippant and just slap in a keyword and move on. Be careful that the new little bucket you add will be a useful one.

As you go on, keywording will become simpler. Type a few keystrokes and choose a keyword that will bring a path and synonyms with it. Maybe do one or two of those for each group of images in the batch you’re working on, and go on to the next one. If you made the right choices at the start, it should become quick and easy.

In upcoming posts, we’ll have How-Tos that take our new keyword list to some of our favorite applications to do some practical work. We’ll start with Photo Mechanic and then move on to Lightroom.

How are keywords working for you? Have I helped? Was this worth twenty minutes and a full cup of coffee? Are you a keywording pro and you want to disagree with stuff I’ve said? Don’t leave it all bottled up inside. Jump in the comments!

Breaking news: It turns out you CAN do a NOT search in Lightroom!

A viewer on my YouTube channel left a comment wherein he explained that you can use a Smart Collection as a workaround for the missing Filter or Find functionality. And here is my recap of his comment:

*Go to Collections and make a new smart collection. You can reuse it, so you can name it whatever you want. I called mine “AA_NOT_SEARCH”.

Smart collections use the same filters that you have in the Filter or Find interfaces, but there’s a little plus sign at the right that you click to add additional filter statements.

*Just click the plus and add a second line.

*Choose “Match all of the follow rules” in the pulldown at the top.

*Use the pulldowns to make your first line be your main search, like “Caption contains words [some search terms]” (Note that “Contains” puts an OR operator between search terms, like “Contains Any Of”. “Contains Words” or “Contains All” are probably what you are looking for.)

*Put your NOT statement in the second line. ” Keywords doesn’t contain [some keyword]”.

*Click ‘Save’. And you’re good to go.

Note that both the Caption and Keywords fields in the first column are under the ‘Other Metadata’ flyout.

*To reuse the Smart Collection, right-click on it and choose ‘Edit Smart Collection’.

Hi Carl,

As a subscriber to David Riecks controlled vocabulary, do you suggest adding/appending my newly created and thought out keywords to that database or keeping them separate? I shoot high school and college sports in the Burlington Vermont (and outlining) area. I would also include sports portraits, team photography and event photography as a description of what I shoot.

Davids’ list only contains a half dozen cities/towns in Vermont (oops, now just remembering to use the location fields, not keywords, for locations). I do think that School names, team names are important metadata for my use and others. So would those keywords and appropriate child keywords be added to the list?

Hi Todd,

What I would do (your mileage may vary) is start my hierarchy, or hierarchies, at the top level in the left column, separate from your existing ControlledVocabulary one(s). I would backup (Save) everything, then Merge in my own file(s), then make final edits with the interface in the Structured Keywords panel. Or, you could build your hierarchies from scratch, right there in the panel. Then backup again. (I’m assuming for some reason you’re using Photo Mechanic here. If you’re using Lightroom, you’ll need to translate as we go along. But the principles are the same.)

I would think the advantages of doing it that way would be that it’s way easier to build a keyword file if it’s to start at the top level, rather than to make it fit into the middle of an existing hierarchy, and I would think navigation would be easier with fewer levels. (As you can see in the illustrations in this post, I did actually build my own this way.)

If you use the Find function, it doesn’t matter where the keyword you seek might be; you get to choose in the Find dialog. But if you navigate to the keyword, then whatever path makes the most sense for you is what you want to build. (You might start at “`MyKeywords”, or you might have one hierarchy for high schools and another for colleges, or one for golf and one for football, for example.)

In your case, place names are commingled with institutional names. “Burlington Central High School” (I made that up) is certainly keyword material. But they might play a game in, say, the CapitalOne Arena in Washington, D.C. In which case, you have a place name that isn’t the location of the photo. So, you’re probably stuck with places in your keywords, one way or the other. Depending on software, “Burlington” might or might not return a photo with that keyword. If you want to be sure that “Burlington” does hit that photo, you would do “Burlington, Central, High, School,”

(Of course, school names (hopefully conforming to style) and playing venues will probably be in your captions, too.)

Now that I’ve brought it up, there’s the matter of “High School”. It’s a style issue, for sure. Your style is probably “High School”, but if there are a few “H.S.” entries, a synonym would help. And “high school” is a category of pictures and would most certainly be denoted in the keywords. But “High School” may or may not be part of the name of the school. “Acme Prep”, say. So, “high school” should probably be a keyword of its own. Same for “college”.

So many fiddly decisions go into a keywording plan.

By the way, if you are using Photo Mechanic, the location fields allow you to chose from a list. I built mine from Census data. (South Florida has about 100 municipalities. Nobody knows the correct names of all of them.)

I hope this helps.

-Carl

Thanks Carl! And yes, I am using PM for a few months now. LR and PS are my down stream editors (in my work flow) respectively. Using PM for culling and exclusive meta.data.adder….

T.

Referring XnView, how many keywords / max. characters can be added to a image, not affecting, without a performance penalty?

Thank you.

In the old IIM standard (and I can’t lay my hands on my copy right this second) Each individual keyword was limited to 64 characters. I don’t recall if there was a limit to the total size of the keyword field. In the XMP, there are no limits.

If by performance you mean search/Digital Asset Management performance, I don’t think it really matters for XnView, because XnView doesn’t really have much in the way of search or DAM functionality.

In terms of XnView writing metadata, considering how tiny metadata is comparing to the image itself, I can’t imagine noticing a difference one way or the other.

If you mean performance as in page load times on the web, each character is a byte, basically. (well, two, if you consider that most fields, like Keywords, appear in both the IIM and XMP.) For most images, the IIM and XMP data blocks are four to eight KB or less, combined, unless an absolutely outrageous amount of metadata is there. The Exif can be a little bloated if it contains over-large previews. Altogether, we’re talking about only a few milliseconds of load time with most normal bandwidth, something on the order of well under a tenth of a second, usually.

I just wanted to say how valuable I found your blog and video. (only the first of the latter sofar). I am only an enthusiast but it is by far the best introduction I have read in many years that I have studied and practiced photography. Thank you.

Thank you very much! It means a lot to hear that I’m helping.

Thank you

Thank you Carl for sharing your wisdom!!! Most appreciated 🙂

I loved your article, very succinct, well thought out, and cleverly puned. Like keywords. Hmm, imagine that?

I am just getting started on stock photography, and have had several images accepted by Adobe stock. A real greenhorn. I have been researching for weeks about keywords, and this is by far the most detailed explanation of how to (and how NOT to) use keywords. You went beyond the rinse and repeat tips and tricks of the common rabble and presented real information with associated thoughts and rationales.

Thank you.

As always, thanks. After months, or maybe years, struggling with the best way to tag my pictures -well, not “my” pictures, but pictures that I collect, just because they’re pretty and I like to look at them. Probably what you’d call “meaningless stock pictures” but then I’m no photographer, but I enjoy beauty- I had already discovered some of these tips by myself, but there are many that would have taken me many a month more.

It never ceases to amaze me how you manage to make your posts funny and a really entertaining reading, while writing about metadata, no less.

I know this blog is meant for photographers, not to the likes of me, but I’ve found very useful information here to help me with my hobby, and I’m very grateful for that.

Why thank you for the kind words! Stay safe!

Carl:

I am using Photo Mechanic Plus for managing my metadata for a collection of about 35,000 images. I find your discussion of Keywording most helpful, but have a few questions with regard to PM+.

With the exception of the Keyword entry, all of the data entry pull-down menus for the searchable IPTC fields are flat (or term) files; none support hierarchical lists. Of the searchable data entry fields (except Keywords), only Title/Object and Headline are logical entries for a description of the subject of the image. The Description/Caption is not searchable. Thus, Keywords appears to be the only choice for a structured, hierarchical keyword subject list.

Let’s say you want to enter information about flowers and horticulture in a structured list as in Keywords. Now say you also have images that depict animals, you use a different hierarchical list, etc., etc. When you look at the Browse menu in the new cataloging system, all of the entries from these different sources are sorted alphabetically starting with the first character in a multiword string unless you insert the entire path in the hierarchy.

This may be OK if you are preparing a list of keywords for an agency or for others who may look at and search for your (really good) images, but if the goal is have keywords that are strictly for your own convenience is searching for images in your collection, this gets to be more than cumbersome.

What to do?

The Title/Object name might be a good place for the descriptor of the subject, but you would have to build a flat term list. But still, your animals and your flowers (to pick only a couple of subjects) get mixed together. Of course, you could always use a prefix descriptor to sort them out, such as animals>mammals>bears and plants>genus>species. A controlled vocabulary would be critical in keeping this all straight.

What am I missing in this discussion? My goal is for my own use. I am not a pro, and I do not sell images to agencies, but I do produce TV shows and/or slide shows for public audiences and sometimes my presentations get put on someone else web site.

You comments would be most helpful.

Many thanks,

Bob Hendricks

Check out my review/How-To for Photo Mechanic Plus. It’s one of the more recent posts, so it shouldn’t be too hard to find. Or just use the search box to search for “photo mechanic Plus”.

The Caption most certainly is searchable. It’s the most important field. It’s where the specific description of what’s in and what’s happening in the picture goes. (In some narrow areas, like stock photos -which often aren’t “real” to begin with – the keywords can be the more important field.) In PM+, next to the search box, in the “star” pulldown, there’s a list of all the searchable fields and what they’re called in PM+ (Which is very handy if you want to do fancy searches against specific fields.)

Keywords are flat by nature. Once an asset is at the point of searching for it, there is no such thing as a hierarchical keyword. There’s just a bunch of potential search terms in a bucket. It doesn’t matter how they got there. If you search and hit one (or three, or however many), that asset comes up in the return. The whole hierarchical keywords thing is only applicable to the process of assigning the keywords in the first place. Photo Mechanic has a dandy tool for hierarchical keywording. (Structured Keywords, they call it.) Adobe muddied the water by coming up with an overly complicated (and dangerous, IMHO) scheme to allow for hierarchical edits of keywords after the fact. But that’s only for editing. Once you get to the search phase, Adobe’s keywords are just as flat as everybody else’s. (And FWIW, Photo Mechanic has a method for editing already assigned keywords that, in my opinion, is safer because it makes you work harder to mess things up.

If you do have a case where a user might need to see a taxonomical string, that needs to go in the caption. It’s bad practice to assume the human beings will ever open and root through the keywords field. Check out my post on the Statue of Liberty postage stamp debacle for an illustration of why this is so.

Title/Object Name and Headline are interesting fields because they are used in very different ways by different organizations. I have written about them before. The standard allows sufficient leeway in the definitions of those fields that this is OK. Most photographers are perfectly safe not bothering with them. If you contribute to a certain organization and they want you to use those fields in some certain way, they will certainly speak up. For most photographers, the caption contains – or should contain – any information that might be headline or object name-worthy.

BTW, You can configure the per-field pulldowns in the IPTC Editor (and Template Editor) to work as controlled vocabularies by going to Edit>Settings>Auto Complete and ticking “…. only allow completions from the field’s own list”. Once you have more than a few terms for a given field, the pulldown functionality gets a little wonky. But I do this for Keywords, for when I don’t want to drag out the big Structured Keywords tool.

I keep threatening to write a stand-alone post on how to write a good caption. Until then, there’s a lot on caption writing in my post on Creative Commons, and there’s a very old post on what each IPTC field is for. I’m sure if I re-did that one, it would be better. But it may be worth a look.

I hope this helps.

-Carl