Photographers should take advantage of Google Images’ new support for rights metadata

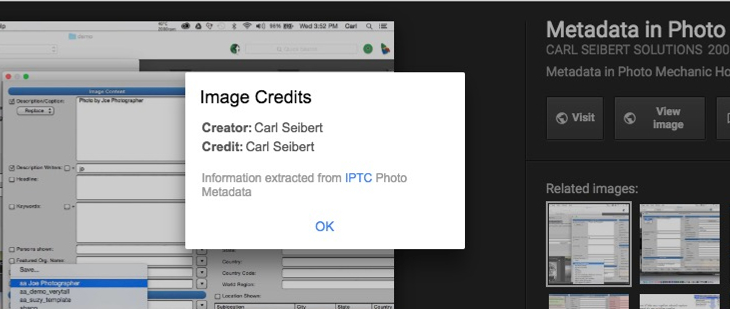

On September 27, Google announced that it would include limited support for IPTC metadata in Google Images. Next to the gratuitous “Images may be subject to copyright” disclaimer, users may now find a link for “Image Credits” if that metadata exists in the photo. They can now see for sure who owns the picture. That is, if, the relevant metadata exists in the image file.

Google will now display to users, at least those who look, the contents of three copyright-related metadata fields – the IPTC Creator, Creditline, and Copyright fields. (The first two are operational now, the latter will be “in coming weeks.”)

UPDATE 11-7-18: IPTC Managing Director Brendan Quinn announced on the IPTC mailing list that Google is now displaying the Copyright field. I confirmed that the field is displayed in the US. By the time you read this, it should be available worldwide.

This is a huge step forward for photographers. But “if” the metadata exists means we have to put it there.

This post is a HOW-TO for putting it there.

We’ll talk about background and general considerations here. And in the videos, you’ll find complete instructions for actually doing the work in specific photo editing programs.

In this blog, I cover a half dozen or so popular programs that we can use, including all-in-one non-destructive editors like Lightroom Classic and ON1 Photo RAW, photo browsing and management programs like Photo Mechanic, XnView, and Adobe Bridge, and good old Photoshop. Others work, too. You can see a list of programs that work on the IPTC’s website, here.

The three fields that Google reveals all contain information that you will never, or rarely, change. Thus, we can take care of them in a template of standing information that you will create and apply more or less automatically to your images. So, the amount of work involved, once you have your template in hand and you have familiarized yourself with your software is essentially – zero.

Download a starter template here. Learn more about importing metadata templates in photo editing programs here.

Always use your template. Always.

Google notwithstanding, it’s vitally important that you ALWAYS use your template! DO NOT try to type repetitive information individually into every picture you make or publish. Human beings are not made to do that sort of work. Especially creative human beings. We suck at it. We are inconsistent. We make typos. Machines are good at it.

What is this metadata of which we speak?

For those of you who are just joining us, “IPTC” stands for International Press Telecommunications Council. They have created a now decades-old and near-universally adopted standard that defines descriptive metadata for digital photos. There are other metadata standards for niche applications, but the IPTC’s is the only one we need to worry about, and is the one Google is supporting.

As you might guess from the name of the organization, the standard was originally created for the news media industry, but it’s applicable to any type of photography.

The IPTC standard defines various fields – lots of them – into which we place specific types of information. You may use a couple dozen or more in your template. But let’s take a detailed look at the three that Google now supports.

Creator

The Creator field is pretty obvious. Sometimes this field is called “Author”, or “Photographer”, or even “Byline”. It’s your name. Nothing fancy, just your name (or names, in the case of a collaborative work). In rare cases, the creator may be an organization, like a studio.

Usually, the creator owns the copyright to the image.

Copyright

The coming-soon-to-Google Copyright (or Copyright Notice) field is just that. It names the for-real owner of the copyright, usually in a form like “Copyright 1999 Josephine Schmoe”, or using the copyright symbol, ”© 2018 Joe Photographer”.

The three elements that should be in a (US) copyright notice are the word “Copyright” (or the symbol), the date of first publication (or creation if the work is unpublished), and the name of the copyright owner.

For works created after March 1, 1989, the use of a copyright notice is optional and its form can be basically any old way you want. You can omit it altogether. But Captian Obvious at the Copyright office points out that there are “advantages” to including one.

Metadata enables honest people

One of the reasons, as per both the Copyright Office and common sense, to use a copyright notice is to enable honest would-be users of the work to contact the copyright owner.

Therefore, I think it is a really good idea to add some very brief contact information in your Copyright metadata field, like “© 2018 Carl Seibert www.carlseibert.com”, or “Copyright 2021 Joe Photographer 123-456-7890” Since Google will pop up this field and not the more detailed fields that hold contact information.

I usually put a couple extra spaces or a pipe between the name and the contact information just because it seems like a good design idea.

Some people add a rights statement like “All rights reserved” to the Copyright field. There are other places in the metadata for that sort of thing. But to each his or her own.

We haven’t yet seen how Google will display this field. In particular, we don’t know if there will be a character limit. Stay tuned.

UPDATE: IPTC Managing Director Brendan Quinn sent a screenshot showing the Copyright field from the standard IPTC test image as seen in Google Images. That field in the test image contains 53 characters. The way the line breaks suggests that Google can display at least 69 characters or so. “Copyright 2092 Joe Photographer 123-456-7890” is 44 characters. Add “joephotographer.com”, count for a couple spaces, and we’re up to 64 characters. So it looks like any copyright notice that doesn’t include an outrageously long name or URL should be displayed in full.

This is where I say that I am not a lawyer and this is not legal advice and if you need legal advice you should darn well hire a good copyright lawyer. Seriously, folks, lawyers need the love, too. Hire one if you need one.

Credit Line

Now we have the Credit field (as Google calls it) or the Credit Line field (as the IPTC now calls it).

This is easily the most misunderstood field in the standard. I have spent fifteen or more years explaining this field to application developers, publishers, and photographers. Or trying my best to explain it. Here goes.

The IPTC standard says that the Credit Line is: “The credit to person(s) and/or organisation(s) required by the supplier of the image to be used when published.” Great. I didn’t quite catch that, did you?

The Credit Line was once called “Provider”. That’s a little more descriptive. The Credit Line is the organization that distributes or is responsible for an image.

If you’re a photographer, the Credit Line is typically your employer.

An example helps

It’s easier with a real example. Tyler Hicks is a New York Times staff photographer. His credit, as published with his pictures is “Tyler Hicks/The New York Times”. “The New York Times” goes in the Credit Line field. “Tyler Hicks” goes in the Creator field.

Sometimes, the organization named in the Credit Line owns the copyright. But not always. Either way, if you are looking for the owner of an image, the Credit Line can be a good clue for where to start.

Over the years, people who don’t understand this field have drifted toward using it for the whole of what should be published as credit for a picture – as in, “Joe Photographer/WidgetCo”.

This makes me crazy. It’s mixing two kinds of data in the same field. Anybody who has worked with a mail merge list that lumps first and last names in the same field knows the pain I’m talking about.

The IPTC has liberalized its definition of the field to tacitly allow for this kind of usage. That irks me a little.

But we don’t know how people will end up using this field in Google Images. Your guess is as good as mine. However users on Google Images turn out to use the field is how we should enter it on our photos. My sensibilities notwithstanding. We’ll have to wait and see. In the meantime, follow your instincts, I guess.

Most individual photographers have never had to bother with this field. Now it looks like we will. If you aren’t working for an organization, just put your name in Credit and move on.

Videos using specific software

Photo Mechanic

Lightroom Classic

XnView

ARVE Error: Invalid URLhttps://youtu.be/--OAUdL4SdU in urlPhotoshop

Each video describes marking up your photos with metadata, and Google Images-friendly metadata in particular, in a popular metadata-capable app.

The videos show the process of actually doing this stuff in specific software, but here’s how it will go in general terms:

If you want to, you can usually apply your template metadata at the beginning of your workflow, as you copy photos from a memory card, or as you import them into a database-driven program, like Lightroom.

If you want to apply your template later in the workflow, you’ll simply select a bunch of photos and apply the template. (Usually, it’s about a two-click process.)

And that’s it, at least as for fields that are the same for more or less every picture, including the Google-blessed ones. Once you have the procedure down and your template prepared, a near-zero amount of effort will put your work in better stead than 97% of what’s out there. (According to this study by copyright protection provider Imatag.)

Captions – We need captions

With Google taken care of, we should definitely go a step further and give our photos captions that specifically identify their content. Google isn’t (yet) showing captions. But there’s more to life than Google.

Much of the power of photography is its specificity.

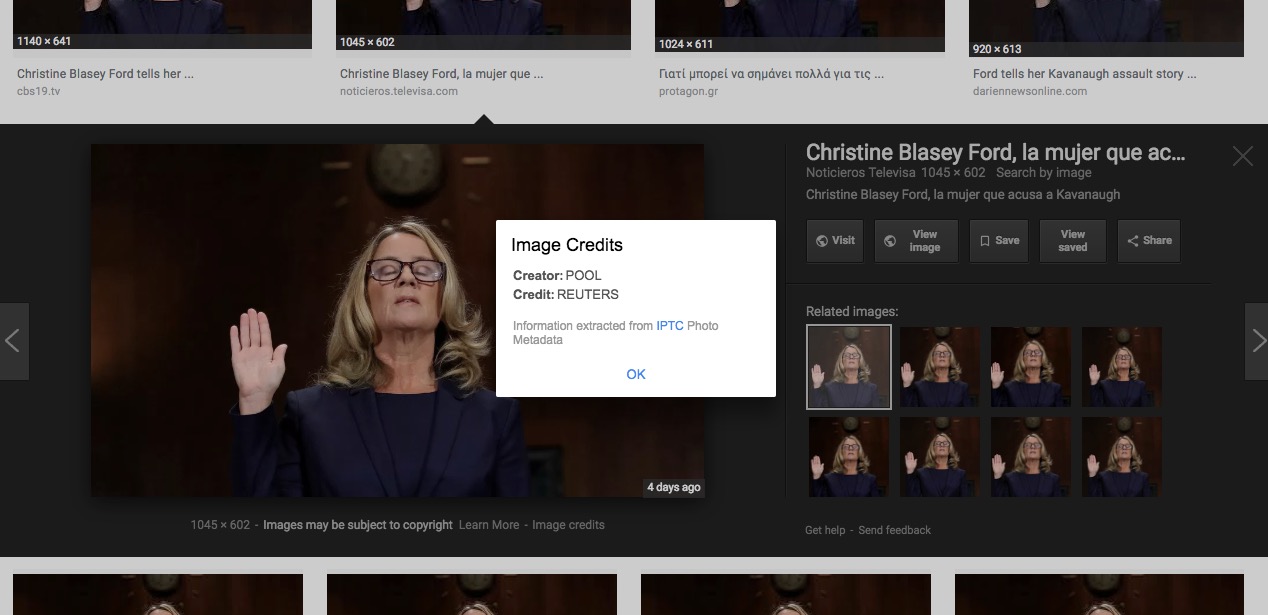

This image deosn’t mean much unless you know who and what is depicted.

Consider the case of Win McNamee’s photo of Christine Blasey Ford testifying at the US Senate. Blasey Ford is huge news in the US as I write this. Her testimony may mark an important moment in US history. And McNamee’s photo carries emotional weight when viewed in that context.

There’s power in that photo if we know what it shows. That’s what captions do. Without captions, whether embedded in the photo’s metadata, printed with the photo on a page, or simply burned into our consciousness, most photos lose their power. Blasey Ford becomes just some professorial-looking lady being sworn in about something, giving testimony on the discount rate or something. The photo just deflates without a caption.

While Google may not display captions, most desktop photo apps do. And very often, a caption is the only metadata a user sees.

Captions are worth some work. Writing good captions is discussed in detail in this post, among others. This link will open a search for “caption” across my site

Keywords can be helpful, too. (To you. Not to Google – yet.) Go here, here, and here to learn more about keywording your photos.

Stuff to consider

If you have a website, please make sure that your site doesn’t strip away metadata from the photos you publish.

Be sure the program you use to write your metadata complies with the IPTC standard. Standards compliance ensures everybody, Google included, is on the same page.

And it means that you won’t lose your metadata when you use a different program to manage your photos later. (And you will migrate to different software. We all will.)

A couple technicalities

The metadata we’re talking about is IPTC metadata, and this particular IPTC metadata is stored in your image’s file in duplicate in two data blocks – the XMP and IIM. Google will look first in the XMP data block and if it doesn’t find anything there, it will use information from the IIM block. If the metadata was written by software that works properly, you don’t need to worry about this. See this post for more on data blocks.

The IPTC has published its own starter guide to Google’s Image Credits. Read it here

And again, we are NOT talking about Exif metadata. That’s a different thing altogether. Google isn’t reading Exif.

Not the silver bullet

Putting copyright (and other) metadata on your photos is no guarantee that they won’t be stolen. Metadata helps honest people behave honestly. Thieves will be thieves. If more people behave honestly, there will be more inhibition against dishonesty. Or so one would hope.

We still need to educate folks that if a picture doesn’t have copyright management information, that doesn’t mean it’s OK to steal it. You will actually find people who think that. And truth be told, there is some logic to the idea. But copyright law just doesn’t work that way, or at least hasn’t since 1989. I have been told that suing people tends to clarify their thinking on this point.

(Personally, for what it’s worth, I do actually think that it would be a good idea to make a copyright notice mandatory; that stripping copyright management information should be a criminal felony; and that people who publish stolen content should be fed to dogs with gum disease. But that’s just me.)

May be?

Google’s ironic “Images may be subject to copyright” disclaimer doesn’t help. “May” be? With very narrow exceptions, every work has a copyright the moment it’s created.

I propose Google help us out by changing the disclaimer to: “You can pretty much bet your life the image you are contemplating stealing is copyright protected and there’s a guy here with a big dog with poor dental hygiene that is going to take a chunk out of your sorry butt if you even think about stealing this picture.”

There’s no snarling dog. And there is a lot to be done. But what Google has done for us is a giant step in the right direction. Let’s take advantage of the opportunity.

Is marking up your images with metadata a new thing for you? Maybe this is your first visit to the blog. Look around. There are lots of resources here. And, if you get stuck, please jump in the comments and ask. We’ll be happy to help.