New website tells where dick pics come from; it’s all about metadata

Dick pics. Film at eleven. This week’s internet’s social, er, upheaval has it all. Bad puns. Check. Click bait. Check. Moral outrage. Check. (I guess.) Metadata. Check. Wait. Metadata? Yup.

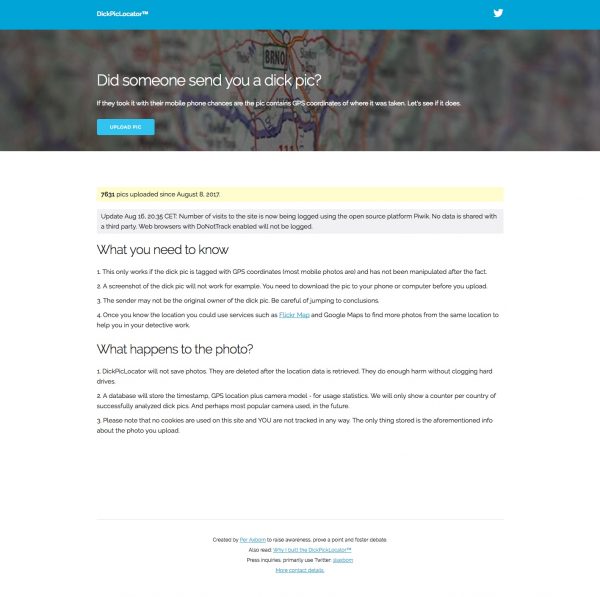

A UX designer in Sweden named Per Axbom was trying to get to sleep and instead awoke with an idea for a new website – dickpiclocator.com. The (un)rest, as they say, is history. (And no, puns aside, I’m not making any of this up.)

Axbom thought that a web-based service that would reveal the GPS location information (metadata. I promised. I won’t let you down here.) of dick pics might inhibit perpetrators of that dark art from, ah, perpetrating.

But Axbom had ulterior motives. His deeper intent was to stimulate thought and discussion about Exif and metadata in general. We’ll get back to that.

First, some background is in order.

Dick pics?

In case you haven’t gotten the memo, dick pics are a new big thing. BuzzFeed has a standing tag for stories about them. At Mashable, dick pic news occupies its own category. Socially conscious artists are hanging shows on the subject as we speak.

It’s all a little outside my frame of reference, but apparently, some truly creepy corner cases aside, it’s about some young men who think the way to win the hearts of young women they correspond with on dating websites is by sending them pictures of their penises. And, apparently, as unbelievable as it may be, some of the said dating services actually don’t strip the Exif data off….. well, you know. And dickpiclocator.com is then able to provide the transgressor’s location.

It’s fairly obvious to me that these guys are not real savvy about metadata. Or about women, for that matter. (And with all due respect to the writer at Jezelbel.com who couldn’t commit to using “his” instead of “their”, I think we’re not too far out on a limb if we demographically stereotype dick pic senders as guys. And not the brightest specimen of the gender, either.)

Most social media strip metadata

It’s only fair to point out here, that most social media platforms strip Exif metadata, and other, more valuable metadata, off pictures they distribute. Facebook, Twitter and Instagram all do this. Facebook does leave your copyright notice but obliterates everything else. So, you need not worry about geo-tagging your body parts on those services. Your worries are more in the opposite direction.

The deeper dive

So there’s the high-level issue. But there’s more. Axbom wrote a 3,500-word Medium post about why he built the site.

1. I want the tool to instigate the moral and ethical discussions that surround the sharing and retrieval of GPS coordinates from photos.

2. I want people to be more aware of the risks they inadvertently may put themselves in by posting photos that contain the GPS coordinates of their homes and the artifacts within.

3. I want people to look at this website, maybe try it out with an innocent picture, and gasp at the accuracy at which it can pinpoint their kitchen table.

Axbom speaks rationally, and at some length, about the issues surrounding transparency and trust on the internet in general, and where metadata is concerned in particular. He wags an accusing finger at hardware and software manufacturers who aren’t as upfront as they should be about what information users are sharing and recording when they use the fancy features of their devices and free online services. His point is well taken.

As true as that is, Axbom contends that, short of an unlikely (at least in this country) show of interest by government, there’s isn’t a lot that can be done to change the habits of big media companies. We need to educate, and to some extent act in the interest of, end-users.

“End users need to become better at making considered choices when sharing online. Geolocation is really cool, but sharing it publicly all the time may not be in your best personal interest. In the end, however, each and every person must make that decision for themselves. I’d just rather it be a conscious decision than an unconscious one.”, he said, in response to my query on Twitter.

(For further reading on geotagging, see an Axbom post on Medium, and one of mine, here.)

All that said, what are we really talking about here? “We” being people who might read this blog.

When we make and publish photos, we need to stop and think about the responsibilities that are implicit in that act. While it’s never a bad idea to repeat a guiding principle, I think we already know that.

On one hand, loyal readers know that there is a responsibility to appropriately label photos with information on their content and provenance for the benefit of whoever might encounter those images in the future. (See my contemplation of the significance of good captions in this post.) On the other hand, when we publish those images, we must consider the context of what we’re publishing – preserving the intent of others’ work, and editing our own accordingly as we go.

What, if anything, should we strip?

By the time in a piece of content’s lifecycle that it’s ready to be published, its Exif data has probably outlived its usefulness. I have argued that, as website operators, we can (usually) safely assume that Exif data just represents wasted

On the other hand, we can safely assume that IPTC information was put there by the author of a work for a reason and it’s on us to preserve their intent. (Not to mention that it’s legally protected in many countries.) So we don’t strip IPTC. There. Simplifying assumptions that work! And that you’ve already read on this very blog.

Might we be more fully transparent and add a statement to our privacy policies or terms of use that says what we will and won’t do with users’ embedded metadata and that we’ll do it on a case by case basis, at our sole discretion, blah, blah? Hmmm. Well, I’m thinking about maybe doing that.

Axbom addresses this point. He points out that the whole idea of CYA policies and EULAs is very seriously broken. He cites a Carnegie Mellon study (well covered in this ‘Atlantic’ article) that puts the opportunity cost of reading privacy policies (just in the US) at an astonishing $781 billion a year. That’s three-quarters of a Trrrrilion dollars. If we actually read all that nonsense, which nobody does. Maybe the terms of service idea might not advance the larger interests of society after all. Let’s put that one on hold.

So there it is. Click-bait-y internet silliness about other internet silliness, an intelligent Swedish fellow who started a worthwhile discussion, an amusing website, and it’s all about metadata.

In my next post, barring breaking metadata news, we’ll talk about something really, really nerdy.