Webmasters — metadata is your friend. Respect it.

We should be able to look at a photo, or another digital asset, and see for sure who owns the copyright, how to credit the photographer, and what the heck is going on in the picture. It’s one thing that the client signed a contract that promises they’ll give you only material that’s properly licensed. Knowing for sure would be another, better, thing.

If you buy a jar of queso dip, it’s got labels, right? You can see what you can use it for, how to contact the manufacturer, and that “best by date”. It seems reasonable that in this day and age digital assets should have labels, too, right?

Turns out they do have. Make that “can have”, If the creator of the asset chooses to write the information in his or her his file’s metadata. And if we look. Sadly, few people even know that we can look at that information. That makes creators less likely to put it there. Which makes it less likely that anybody looks, which……….. It’s one of those vicious circle thingies.

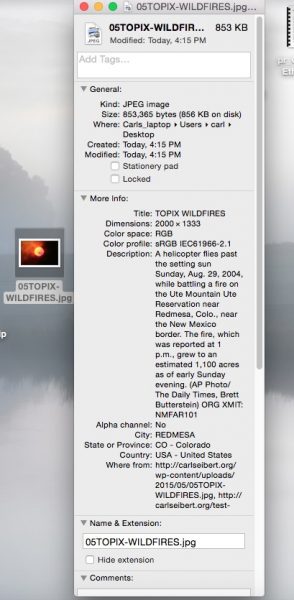

Good news: it’s not hard to see metadata. Your operating system (Windows, Mac, and Linux) displays captions in its file manager. Image editing software, from fancy and expensive to simple and free, can edit IPTC metadata. Command line utilities can manipulate it on the server.

But there’s bad news. Let’s say if a conscientious photographer does write his or her copyright and contact information and a good caption on a photo, will everything be OK? Ah, maybe. The chances are good that the first website that gets its hands on the poor photo will strip all that information off.

Back in the day, stripping off an image’s metadata actually made sense. That was when the rule of thumb was that landing pages had to be less than 40 kilobytes, back before they were even called landing pages.

That was then. Now it’s different. The internet is flooded with works that have come asunder from their copyright notices and captions. They would be useful if we knew what they are, but we don’t, so they aren’t. There’s a feeding frenzy of copyright infringement and plagiarism and ethical people are concerned, very concerned.

It would be great if critical information was embedded in every photo that was sent out into the internet world; if that information stayed with that asset forever, and we knew just what we were dealing with every time we picked up a photo. Let’s make that (start to) happen.

We need to make some stuff happen

We need to:

Encourage creators to properly document their works. (See my rant on why photographers need to do a good job with metadata.)

And…

Ensure that documentation is not destroyed, so it can travel with the work wherever it goes.

As soon as we publish them, digital photos begin traveling the web at the speed of a right mouse button.

As web developers, designers, and site owners our part is to make sure that neither we, nor our CMSes, ever unnecessarily strip metadata off works.

But wait! “Unnecessarily” suggests that there’s nuance, and nuance suggests that there is annoying underlying technical complication (and acronyms). Of course, there is! This being a full-disclosure kind of blog, we’ll unravel that. Well, some of it. I’ll spare you the low-level stuff. We’ll discuss that in depth later.

Back in the day, there were two reasons for stripping metadata: load time and privacy concerns.

Back then, 8KB one way or the other materially affected load time. Today, that’s like five one-thousands of a second for a user with seriously mediocre internet service. Not a big worry.

I said eight kilobytes because That’s about how much metadata we really need on a photo. That’s the stuff that could be useful for saving the world. There is, however, more.

Really important metadata and less important metadata

Basically, there are a couple of flavors of metadata written into photos.

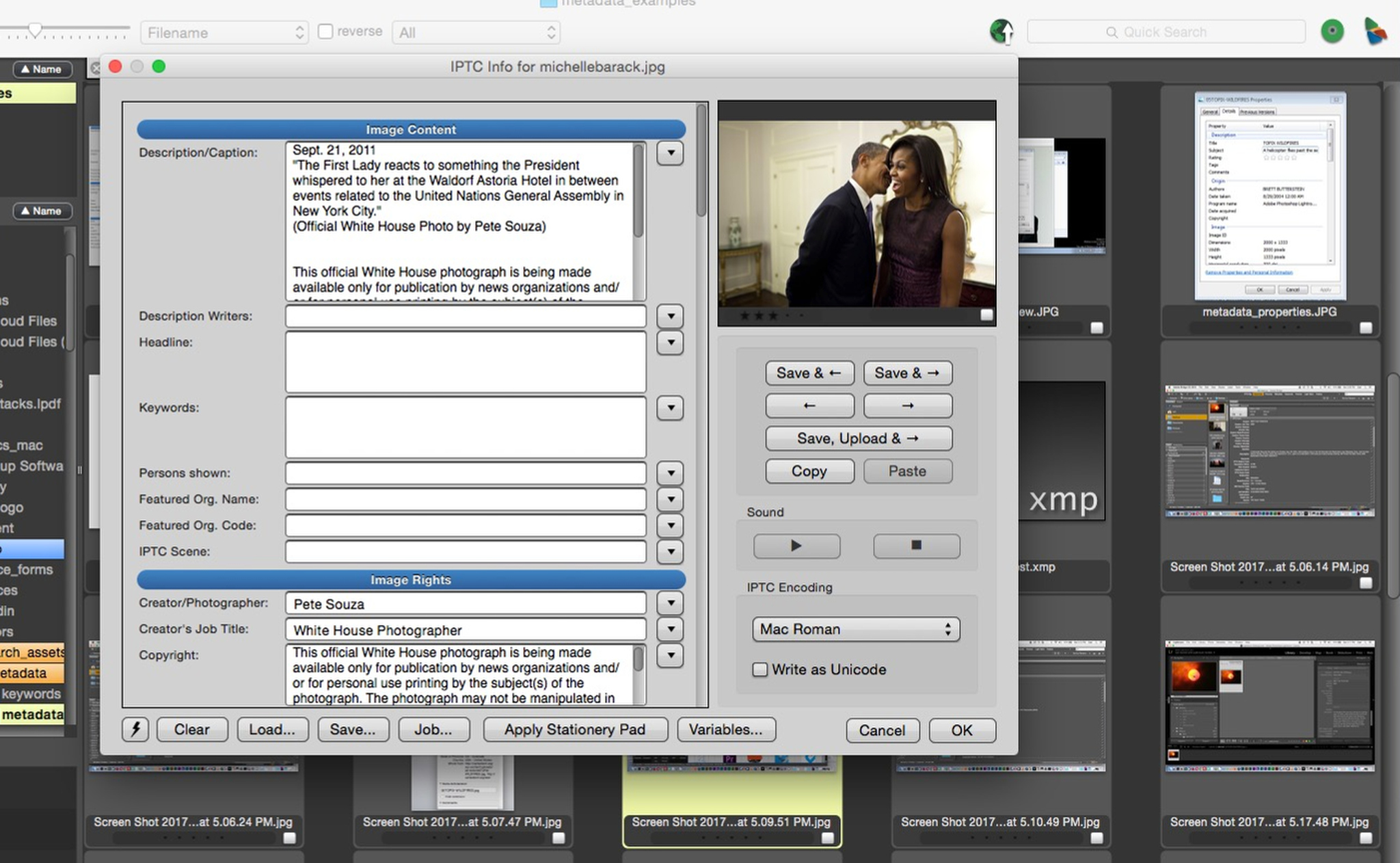

There’s IPTC metadata. That’s the world saving stuff – caption, creator, and copyright information. IPTC metadata appears in a file twice (usually), once in its old-timey

(There’s also the possibility of other, non-IPTC, data written in XMP format. It’s not very big, either. We’ll just skip that, since in the context of publishing a picture on the web I can’t think of a reason why we would care one way or the other.)

Then there’s Exif metadata. Exif data is written by the camera when a digital picture is made. It’s mostly boring logging data. It records the camera model, serial number and the settings used to make the photo. EXIF also can include GPS data showing where the photo was made. That could identify the user. We’ll come back to that in a bit.

JPEG files can also have an embedded JPEG thumbnail. We’ll leave musing about what the heck for to another day. Said thumbnail, if present, can take up twenty or thirty-ish kilobytes.

The good news here is that the useless and potentially enormous thumbnail resides in

In a future post, I’ll talk about exactly how, and software we can use.

Consider before you strip

Exif or otherwise, in our strip-or-don’t-strip deliberations we should pause to consider some more stuff: legality and privacy.

Here’s where I say that I’m not a lawyer. I don’t play a lawyer on TV, not even YouTube. When in doubt, talk to your own lawyer! You know the drill.

Under the Digital Millenium Copyright Act, it appears to be pretty seriously illegal to remove or alter “copyright management information”. Statutory damages are set at between $2,500 and $25,000 per occurrence.

(1) intentionally remove or alter any copyright management information,

(2) distribute or import for distribution copyright management information knowing that the copyright management information has been removed or altered without authority of the copyright owner or the law, or

(3) distribute, import for distribution, or publicly perform works, copies of works, or phonorecords, knowing that copyright management information has been removed or altered without authority of the copyright owner or the law, knowing, or, with respect to civil remedies under section 1203, having reasonable grounds to know, that it will induce, enable, facilitate, or conceal an infringement of any right under this title.

(c) Definition.—As used in this section, the term “copyright management information” means any of the following information conveyed in connection with copies or phonorecords of a work or performances or displays of a work, including in digital form, except that such term does not include any personally identifying information about a user of a work or of a copy, phonorecord, performance, or display of a work:

(1) The title and other information identifying the work, including the information set forth on a notice of copyright.

(2) The name of, and other identifying information about, the author of a work.

(3) The name of, and other identifying information about, the copyright owner of the work, including the information set forth in a notice of copyright.

…[skipping a couple items that don’t apply to pictures]…

(6) Terms and conditions for use of the work.

(7) Identifying numbers or symbols referring to such information or links to such information.

That’s pretty blunt stuff for something that politicians wrote.

The stuff they define as being “copyright management information” would be found in the IPTC fields for Caption, Title, Author, Copyright, Rights Usage Information, and various contact information and PLUS licensing fields. Possibly in Special Instructions, as well. That’s enough of the IPTC fields that we can pretty safely assume that the path of least regret here is to be very cautious about messing with any IPTC data.

You can do whatever you want with the copyright management information on works to which you own the copyright, of course. Or, if the copyright owner gives you permission, you may strip away. Some sites, like Facebook, include language in their Terms of Service that grants them permission to alter CMI on photos. But it’s worth noting that Facebook does leave the copyright notice and the creator’s byline on pictures. They strip out everything else but leave those two fields alone. That says something.

Privacy can be a consideration

Then we have privacy. Everybody nowadays has their undies in a bunch about privacy. Some concerns are legit. Some are silly. But still, we need to think about this.

In the EXIF, there’s that potentially identifying GPS information. Geotagging information can be useful. You could, say, automatically display a map with travel photos. (Or leave the possibility open for the next person who uses that picture.) On the other hand, if you’re not going to mention where a picture was made in a caption that’s visible to visitors, it might be nice to delete the GPS info. I can imagine cases where that would be justified, like maybe a picture of a fisherman at his favorite top secret fishing spot, for example. How convenient it is that GPS info lives in the rather expendable EXIF and not near the DMCA-protected copyright data in the IPTC!

Watch a video demonstration of applying IPTC metadata to a bunch of pictures

And what about identifying information in the IPTC metadata?

When we consider information in the IPTC data, the first point to consider is that the photographer deliberately put it there. Do you trust that he or she did their job properly? The very fact that the information is there says something positive about the photographer’s professionalism.

Identifying is exactly what the caption is there to do. Specificity builds your authority. Barring pretty unusual circumstances, you want to tell your visitors exactly who is shown in a photo, what they’re doing, and in what context.

Now, you may decide for some privacy-based reason or another not to publish

information that is in the metadata with a photo. Then you might want to edit that same information out of the metadata, too. You might be concerned about doxing, for instance.

It’s a case-by-case thing. But honestly, it’s not something that comes up often. In my career as a newspaper photo editor, I published dozens of photos a day. I’d kill a photo or write around somebody’s identity a handful of times a year.

What I’m saying here is always look before you leap and use good judgment for each image you publish. There’s software that makes it easy. I’ll post more on what’s out there and how to use it later.

(General purpose ethical note: If serious privacy concerns are making you even think about whether to withhold all or part of someone’s identity, the ethical path of least regret is usually not to run that picture at all. It’s serious business. One day, I’ll devote a post to this, too.)

So, the big takeaway here is that we should avoid tampering with IPTC data, but we may want to delete EXIF data (and its potentially huge thumbnail).

Systems issues. Or automation might not be your friend.

Content management systems tend to strip off metadata by default. It’s an extremely rare case when that’s a good thing. We really need to make them stop.

Sadly, many websites, including all the big news sites and social media sites, delete metadata. I know why this is. I was there when it happened. All the photos used on professional grade news sites have metadata embedded. Many of those sites create their own images. In the metadata of those images, there may be proprietary or identifying information that might not be at all suitable for publication. (And, yes, of course, there was once a grand mistake, followed by a grand legal mess of the sort that gets publishers’ attention.) That’s when everybody in that business decided to strip out metadata programmatically, rather than simply being careful with each image. The assumption then was that those sites were altering works to which they owned the copyright, so no blood no foul. But who employs full-time staff photographers anymore?

If your content management system is automatically stripping metadata, you should consider making it stop. Compare the cost of paying a developer to fix your server to the cost of paying a lawyer to make a copyright suit go away.

Then there are the CMSes that the rest of us use. WordPress, for example, is the world’s most popular CMS. Over a quarter of all the world’s websites run on WordPress. WordPress only partially honors photo metadata.

When a photo that has a caption is placed on a page or post in WordPress, the caption is automatically formatted and placed on the page with the picture. So, good on the making-it-easy-see-metadata front. (And the making life easier for people who build pages front, too!)

But when a photo is uploaded to WordPress, by default, four versions of the file are put on the server. The files are made at various sizes, to accommodate devices with screens of varying resolution. Only one of the five files has metadata on it! Ouch. Granted, the file with metadata is the biggest one, which is generally served when a user clicks on a picture for a larger view. That is the version most likely to be grabbed by someone who wants to – legitimately or otherwise – reuse the picture. But still, ouch. We have work to do.

Note: WordPress, by default, actually prefers to use the ImageMagick image processing library, which does honor metadata for all of the sizes of images. But ImageMagick is not necessarily installed on your host’s server, and if it is, you have to enable it. Like I said, work to do…

There is a workaround. But workarounds require extra work and can only be performed by people who are well informed and technically savvy. (The readers of this blog, let’s say.) That’s good news for “us”, and a tiny first baby step toward saving the world. I’ll post a how-to shortly.

Insist that your server not do anything you might regret later.

Look carefully at every picture before you publish it. Distrust the ones that don’t have good metadata. Heed what the metadata says in those that do.

Yes, we can do our bit to turn the tide to protect content creators’ rights, keep ourselves out of copyright trouble, preserve history, and save ourselves some time and legal exposure. But there’s work ahead of us. Let’s do it!

I’ll pass on how-to information in future posts. We’ll look at software, legal issues, and best practices. If you make pictures, you can take a look at my companion rant exhorting photographers to put proper metadata on their pictures. It’s already accompanied by some how-to information and a video showing just how quick and easy it is to do the (copy)right thing.

I’d love to hear from you. Please post in the comments, or click the “contact” button!