Agency sues celebrity over paparazzi photo; copyright infringement and destruction of CMI claimed

A photo agency has sued clothing mogul and former pop singer Jessica Simpson for copyright infringement and, of more interest to the readers of this blog, removal of copyright management information (CMI). Photo agency Splash News alleges in a lawsuit filed in federal court in the central district of California on January 23 of this year that Simpson posted on Instagram, and later Twitter, a photo owned by the agency.

According to the lawsuit, photographer Humberto Carreno was working for Splash News when he made a series of photos of the celebrity leaving the Bowery Hotel in New York City. The photos were then licensed to The Daily Mail, which published them on its website on August 9, 2017. (Note that the timestamp on The Daily Mail website says August 8) Within hours of The Daily Mail’s publication of the pictures, “Simpson, or someone acting on her behalf” copied a photo from the newspaper site and posted it on Simpson’s official Instagram and Twitter accounts, the suit alleges.

The suit seeks damages for copyright infringement and, additionally, for removal of copyright management information from the photo.

Removal of CMI alleged

The photos as seen on The Daily Mail’s website bear a watermark with a copyright notice at the bottom of the picture. According to the suit, Simpson, or a person acting for her, removed the watermark (presumably by simply cropping it off the picture) before posting it on Simpson’s social media accounts. And, “…removal of the CMI from the Photograph was intentional, and defendants’ distribution of the Photograph was with knowledge that the CMI had been removed without authorization, which further subjects defendants to liability for statutory damages under 17 U.S.C. § 1203 in the amount of up to $25,000. “, the suit claims.

Watch the video version of this post

We don’t know from the lawsuit which of the photos of Simpson published by The Daily Mail is the subject of the suit. The picture has been deleted from Simpson’s social media accounts.

As we can see on The Daily Mail site, here, three Splash News photographers shot Simpson that day, apparently on two occasions, and Carenno’s name doesn’t appear on any of the photos. According to Splash News Editorial director Aaron St Clair, “Many [of the agency’s] photographers operate under an alias, agency name, or simply do not wish to be credited personally for their work.”

CMI is…. metadata

Section 1202 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, as readers of this blog probably already know, makes it illegal to intentionally remove or alter copyright management information, or distribute a work so altered knowing, or having reasonable grounds to know, “that it will induce, enable, facilitate, or conceal an infringement”.

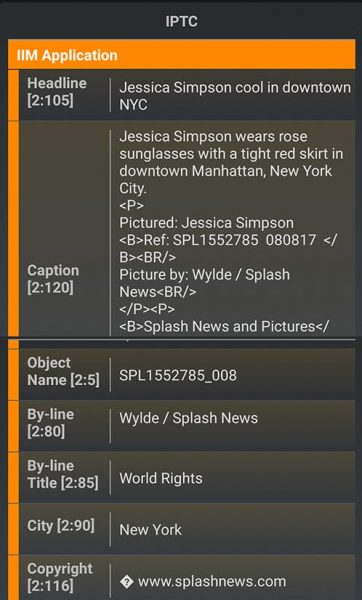

Copyright management information, as defined by the act, is basically core IPTC information – the author’s name and copyright statement, the description or title of the work, and “Identifying numbers or symbols referring to such information or links to such information”.

CMI is “…conveyed in connection with copies … of a work … including in digital form”. It’s metadata, in other words. Metadata, as we know from real life, can be embedded in a work, a la IPTC, or it can appear somewhere on the face of the work. (Remember the metadata scrawled on the front of the old print in this post.) Or it can appear in relation to a work, like a copyright notice printed near a picture in a printed publication. Courts have ruled that watermarks qualify as CMI.

Watermark CMI claims are easier

While 1202 doesn’t allow an accused evil-doer to escape justice by some of the loopholes that the main copyright act does, it does impose the burden that an aggrieved content creator must prove that the skullduggery was intentional. And proving intent is hard to do.

I assume the matters of proving knowledge and intent have so far inhibited content creators from pursuing CMI claims based strictly on stripping embedded CMI from image files.

On the other hand, it’s pretty hard for a defendant to claim that cropping away a copyright notice on the face of a photograph was anything other than knowing and intentional. Thus, we have lately seen lawsuits (and recoveries) based on destroying CMI that was plainly visible.

CMI rulings have changed over time

Over time, the courts have interpreted section 1202 differently, with the interpretations tending to become broader (and saner).

(This is where I disclaim that I’m not a lawyer and that you would be out of your ever-loving mind to construe opinions expressed in this blog as legal advice. It’s also where I can point out that the scholarly analysis of section 1202 you might find on the web is largely written by lawyers, who have to appear in front of judges, and would therefore not say “judicial craziness” if they had a mouth full of it. My opinions may not be as authoritative as theirs, but they can be a bit more, ah, direct.)

Early decisions on CMI tended to aver that to be CMI, CMI must be some sort of mysterious code, only to be read and understood by machines. The logic in those decisions bordered on the fantastic, in my opinion.

A couple judges interpreted 1202 “in the larger context”, or some such nonsense, of section 1201, which is about the circumvention of Digital Rights Management (DRM) schemes. That’s an entirely different subject. (Remember DRM? How nostalgic.) Conflating the two is like comparing the specifications of a cement mixer with those for a motorcycle and saying, “This thing can’t be a motorcycle because it doesn’t have a rotating concrete drum.”

Trend has turned in our direction

The DMCA was being written in the mid-nineties. Back then, DRM, embedded metadata, and the internet itself were pretty mysterious to the average person/lawyer. But the first CMI cases were heard around 2006. By which time everybody pretty much should have known better.

Rather than simply read what the law said (a “textual interpretation” in lawyer-speak) some early judges sought to divine “legislative intent”. (Today, you could read “lobbyist intent” and not be too far wrong.) They then applied (or didn’t) 1202 accordingly. As silly as that was, I do have sympathy. There is a considerable sense of cognitive dissonance when one first confronts section 1202. 1202 clearly is about protecting content creators. The overall mood of the DMCA is about protecting corporations from content creators.

Thankfully, more recent CMI cases have been decided based on much broader, and at the same time, more literal interpretations of 1202. Read about an iconic one here.

What this case might mean for us

Which brings us back around to what insights we might glean from Splash News v. Simpson.

More and more content creators are including CMI claims in their copyright infringement suits. Millions of people will read news accounts that mention CMI as a result of Simpson’s celebrity. Those are encouraging developments.

While I am not aware of any successful recovery based on the destruction of CMI solely in embedded metadata. But, I feel instinctively that has to be in the pipeline. We can wait and hope.

In any case, a CMI claim is an important avenue to pursue in a copyright action, if possible. It opens the door to collecting significant damages for the CMI violation even if the infringer slips the noose on punitive damages for the infringement itself. (Which is pretty easy to do.)

(If you know of a metadata-based CMI case, either involving images or music, please let us know!)

It’s important that creators embed proper metadata in any image they publish for a lot of reasons. Potential copyright actions remain just one of those reasons.

Indeed, Splash News, in addition to the watermarks, embeds metadata. “All our images are copyrighted. When images are downloaded from our site, that metadata including the copyright field, headline, caption etc, remains on the images.”, says St Clair.

Include metadata (CMI) for many reasons

Does proper metadata guarantee that you can make a successful CMI claim? Absolutely not. But it doesn’t hurt. And you should label all your work properly anyway.

As a photographer, I wouldn’t necessarily advocate putting visible watermarks on pictures. It seems like defacement to me. But your situation is, well, your situation. It’s an option. If your situation involves social media sites that are known to strip CMI, then visible CMI on the face of the image might be a good idea indeed.

If you sell licenses to your photos, you might want to think about incorporating a no-metadata-stripping clause in your delivery contract. Your good work marking up your images goes for naught if your client strips off your CMI.

And what of the chance that your picture floats around the internet and becomes an orphan work?

To date, grassroots artists’ organizations have been able to hold off the corporations trying to get an Orphan Works bill through Congress. Will we be able to keep the wolves at bay forever? Who knows? But orphan works (lower case) is a real thing today regardless. The fact that grabbing up unlabeled works off the internet isn’t legal doesn’t seem to prevent people from doing it.

Resolve to do the right (meta) thing

It doesn’t matter what particular motivation nudges you to start properly labeling your work. You’ll glean a bunch of benefits and no downside. If this lawsuit “sells” taking proper care with CMI to a wider audience, then bless Jessica Simpson and Splash News. (Bless whichever one is adjudicated to be in the right more than the other, please.)

What if you’re a publisher, or if you manage websites?

If the allegations in Splash News’ infringement suit turn out to be true, Splash News’ work was lifted not from Splash News directly, but from The Daily Mail, which had licensed and published it.

The Daily Mail did preserve the watermarks on the photo in question. That will no doubt help Splash News’ case. On the matter of preserving the metadata that St Clair says is included with every photo the agency distributes, however, the news is not so good.

When I visited on my computer the Daily Mail page containing the photos, none of the Simpson photos still had their (presumed) metadata. Oddly, when I visited on my phone, I saw some metadata. The for-phone version of the page featured a photo that was a composite of two of the pictures. That particular photo retained what appeared to be a full set of metadata. Others that I looked at carried only an IPTC Credit field. Very strange.

I’m sympathetic to the reasoning that news sites used, way back when, to decide to strip metadata from photos. The sites owned the copyright to most everything they published. Pictures online were low resolution. Everybody assumed they would be stolen and nobody much cared. Certainly, nobody foresaw that trillions of unlabeled photos would float around the web for all eternity. That was then. Today we know about those things. The Daily Mail and every other site on the web should preserve metadata, inlcuding copyright owners’ CMI, if they’re not already doing so.

Keep karma on your side

If you publish others’ work, you could be the vector by which that work is stolen. Legality aside, you have a moral obligation not to “induce, enable, facilitate, or conceal” the infringement of somebody else’s work. You don’t want your website to become a smorgasbord for infringers. It’s just not good karma.

Check every picture you publish for CMI in the metadata. Consider making it a policy to insist that contributors provide proper metadata on their images. (And don’t strip it away!) That metadata may protect your contributors’ copyrights. And it will certainly help you out managing your files.

What about legally?

Could you be held liable for stripping metadata?

Well, if you publish an image you stole, sure. You’ve ticked every box in the law’s list of no-no’s.

But what if you didn’t infringe the image yourself, or didn’t know it was stolen?

Well, read section 1202 yourself, here and you tell me. Could “having reasonable grounds to know” be construed to include abetting an infringement through negligence or sloth? I don’t know, maybe. But it doesn’t matter. It’s simple. Don’t strip metadata or destroy CMI and don’t worry about it. Preserving copyright owners’ CMI is the right thing to do regardless of the law, and it’s easy enough.

Publicity is a good thing

The publicity from this case can raise consciousness about CMI for website operators and content creators everywhere. That can’t be a bad thing. Maybe it will be the nudge needed for some of them to make the right choice about metadata.

Have you ever had a work infringed? Was the situation resolved to your satisfaction? Unburden. Share your experience in the comments.

US and international creatives who choose NOT to timely register their media with the US Copyright Office should, at the very least, affix CMI to their creative media to retain some legal options against (willful) infringers located in the US. I’m seeing more and more US copyright litigators pursue CMI violations.

Two particular US cases dealt with CMI removal: Murphy v. Millenium Radio Group LLC and McClatchey v. Associated Press; see http://www.photolaw.net/did-someone-remove-the-copyright-notice-from-your-photograph.html