Your phone can recognize your underwear; well, sometimes

iPhones know what a brassiere is. Ohmygawd! And on a good day, the phone will recognize one when it sees one. Ohmygawd! A Twitter user noticed last week that the AI image recognition-equipped Photos app on her iPhone would return results from her store of photos if she entered “brassiere” in the search function.

Well. A ripple across the time-space continuum ensued. Tongues wagged. On Twitter twits tweeted. Tech bloggers blogged. (Ahem. Including this one, apparently.)

….the hype happens when a technology is in the “just works on demo content” stage…. Those of us who need to do useful work tend to yearn for the day when the new technology matriculates to the “just works” stage.

At the highest level, this event shows us stuff that we probably already know: The internet is basically a place for fourteen-year-boys. Terrible puns will continue to plague the world (just you wait!). People pay good money for software and then they’re shocked, shocked!, to find out what it does a year after the fact.

And often, that software doesn’t do what it does terribly well. The developers might not have put forth their breast effort. (There. We promise bad puns. We deliver bad puns. And in a timely manner!) But if we drill down a little, peel away the ….. oh, never mind… it’s probably a good time to talk about Artificial Intelligence and it’s would-be impact on adding metadata to images.

We can dream

If we close our eyes and dream, we can envision a world in which machines will take over the drudgery of keywording. My 50,000, mostly untagged, family snapshots magically become organized. Organizations that haven’t kept up with their metadata will be able to migrate to digital asset management systems painlessly. The mechanical help will mean that professionals – and you and I for that matter – will be able to keyword consistently over time.* And that’s not to mention all the joy image recognition will bring to searching.

It all sounds like Artificial Intelligence image recognition nirvana. And you can’t walk down the street today without crashing into developers, like Apple, falling all over themselves to include AI image recognition in their products.

(Developers tout this technology under a variety of names – “Artificial Intelligence”, “machine learning”, “cognitive image recognition”, “facial recognition”, “auto-tagging”, “deep learning”, “deep neural networks” and clever made-up brand names. It all amounts to similar functionality: a computer learns, or is flat-out told, what things look like and later tries to recognize them.)

Video from IBM promotes the company’s AI auto-tagging feature in a DAM system.

The buzz is everywhere

Adobe’s just announced reimagining of Lightroom (coverage here as it unfolds) will feature the company’s “Sensei” AI technology. (Lightroom already recognizes faces.) Apple’s newest products automatically assign searchable (but hidden) keywords as you shoot your photos. Google Photos, and thus your Android phone, if you so choose, does the same thing. There are auto-tagging features appearing in Flickr and countless other photo storage services and Digital Asset Management systems. University and corporate research projects are exposing demo sites where you can test drive advances in the technology.

But is any of this useful right now? That is the big question.

“Just works on demo content” vs “just works”

In software, the hype happens when a technology is in the “just works on demo content” stage. Which is unfortunate in that it makes easily excited people, well, excited. Those of us who need to do useful work tend to yearn for the day when the new technology matriculates to the “just works” stage.

So, does this stuff “just work” yet?

Some practical results

If we’re talking about comparative search functionality, the answer is yes.

Where simply matching a training image to subject images amounts to understanding, we already see practical results.

We can show a search engine – like good old Google – an image and ask it to find images that match or are similar. We (or the NSA) can show a machine a face and it will return pictures of people who might be that person.

Several modern photo management programs can be pretty effective at identifying your family members if you help them out by explaining who’s who.

Indeed, when I logged onto Google Photos to research this post, a popup asked me to identify my face from a selection of possibilities. I chose my Google profile headshot. (Gee, you’d think Google would already know about that one, wouldn’t you?) Now, I can search for “me” and be rewarded with a great ego-justifying return of photos of – me.

On the other hand

But if we are talking about cognition – the ability to understand the semantics of a picture and tell us what’s in it, or what it means – naw, the answer is pretty much “not yet”.

(This BBC story suggests that if your AI systems hangs out with the wrong crowd, not only will it learn poorly, it could be brainwashed.)

Testing the waters

Let’s take an unscientific tour of some currently available image recognition and auto-tagging offerings and see what happens.

For a more disciplined sampling, take a look at this.

I don’t have an iPhone, and I try as hard as I can to avoid the Apple Photos app on my laptop, so my first stop was my own Google Photos account. There isn’t huge dataset here, just the automatic backup of photos from my phone and some miscellaneous pictures, demo material and stuff that has been shared with me.

In the spirit of the moment, I tried “ brassiere”. Google Photos returned two photos. One was a friend-of-a-friend who is a fire performer, wearing a bra-like top (think Princess Leia and Jabba the Hutt). The other was of the Florida Panthers cheerleaders, in bikinis. OK fine. Close enough.

In the list of four thousand scenes and objects that, as of last year, Apple had allegedly programmed its Photo app to recognize, my eye fell on “Bachelor’s Button”. Pretty sure I didn’t have any of whatever those are in my Google Photos, but I thought maybe “buttons” would be in keeping with the clothing theme. (It turns out Bachelor’s Button is a plant. Thanks, Google.) This is what returned:

OK then. Three headshots of random guys, one of whom is me, wearing shirts with buttons; a woman, at night, wearing sunglasses and a gardening hat while holding drinks in silicone glasses (???); a phone camera picture of the collar of a golf shirt; and a wonderful picture by Andy Newman, that I’m always happy to see, of a racing boat with a helicopter that has exactly nada to do with buttons. But what a great photo!

Three of the choices were pretty clever. Two were waaaay out in left field.

What are we doing?

Hmm. Now this might be a good time to stop and think about how we learn how to recognize stuff in pictures. Let’s assume that we teach machines, or machines teach machines, more or less the same way.

Think about the Eiffel Tower. As a kid, you probably learned to recognize the Eiffel Tower by associating a picture of it with some metadata. Maybe in a book. Maybe the metadata was oral – a parent or teacher saying, “this is the Eiffel Tower.” You could then recognize the Eiffel Tower as either the subject of a picture or as an element within a picture.

Thus, you would also know that a cityscape that included the Eiffel tower was Paris, France. (Or Las Vegas, or some other place where there might be an ersatz Eiffel Tower.)

Over the years, we humans build up a tremendous reference library of associations between images and objects and concepts. We can then use the processing power in our noggins to put the bits and pieces together to understand pictures. (For the moment, we will assume our processors to be keener than those in phones. Or most phones, anyway.)

That list of four thousand keywords in the Medium post I mentioned above would represent the things that the then-infant Apple app had been exposed to, minus a bunch of synonyms. That’s not a big dataset. Then the poor little brain in a phone would simply try to recognize similar elements and assign keywords accordingly. We would expect – correctly, if the “brassiere” silliness is representative – the results to be kind of crude.

Big data

The server-based Google system, on the other hand, has billions of photos available to teach its artificially intelligent robots and should be able to learn faster. But still. A helicopter and a boat? A woman with incongruous apparel and dinnerware? Buttons? We still have a ways to go.

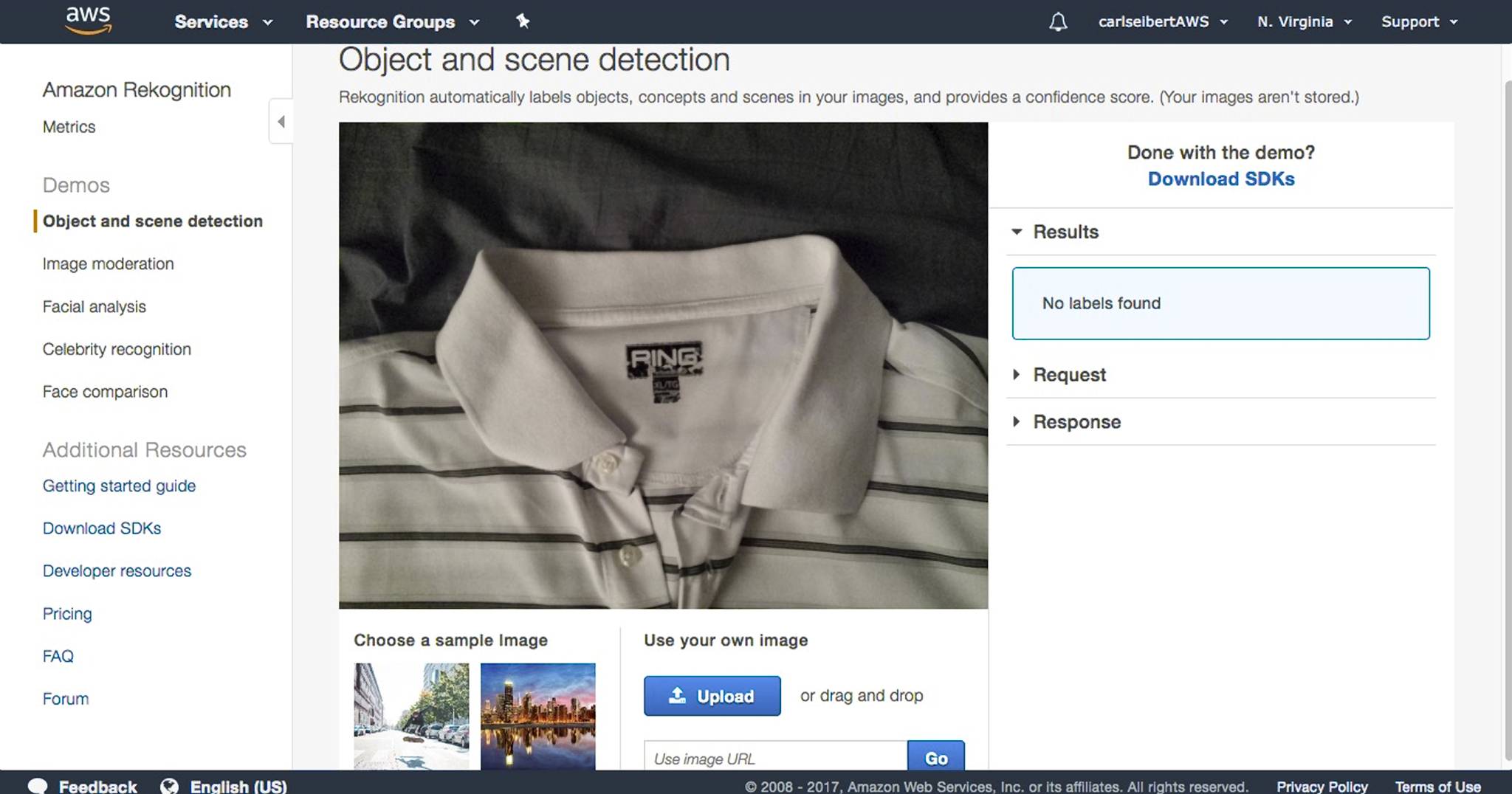

I took my golf shirt collar picture to some image recognition demo sites.

Image recogition systems test drive

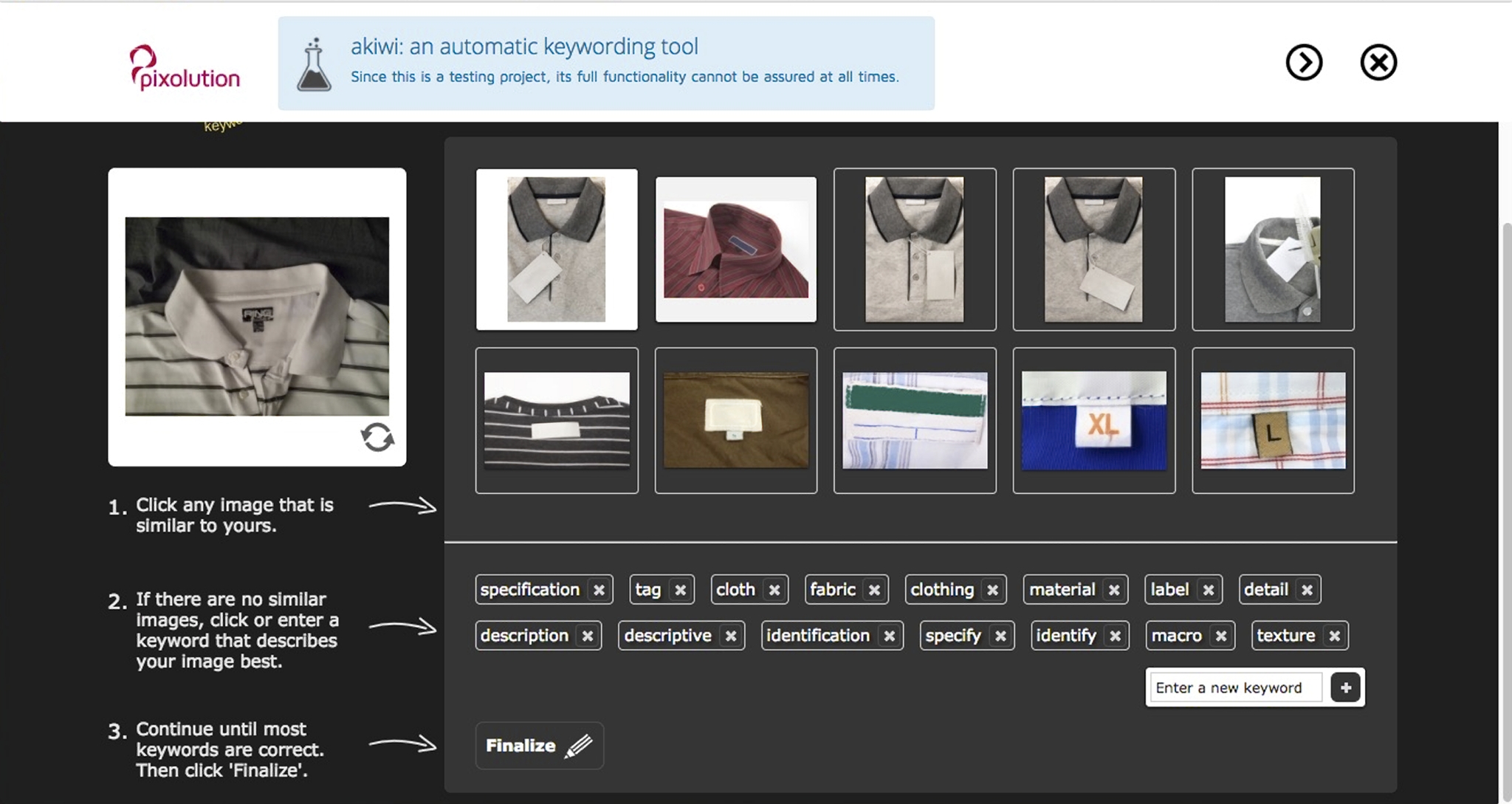

Here’s akiwi, which looks, at least at first blush, like a useful concept: an interactive AI keywording tool. Look at the keywords. We’re missing the big picture here, guys. It’s a shirt! Would any of those keywords be particularly useful to find that image later? Probably not.

Now, proper metadata, in the form of a caption would tell us what the significance of the shirt collar is, what the pertinent details are, and essentially why the picture was made. That’s semantics, in search engine speak. That information would serve later to return the shirt picture to a human searcher who was searching in a context in which the shirt would be appropriate. Where text is concerned, the search engines are already all over this stuff.

Good keywords might return the shirt to a searcher who was looking for golf shirt collars in a context that the caption might miss. Properly assigning those keywords would require some subjective and precient judgments involving the shirt in context in the collection it lived in, what future searchers might be seeking, and how they might go about looking. I have no doubt that machines will one day learn to be pretty good at this stuff, but today’s results still seem awfully crude and not terribly useful.

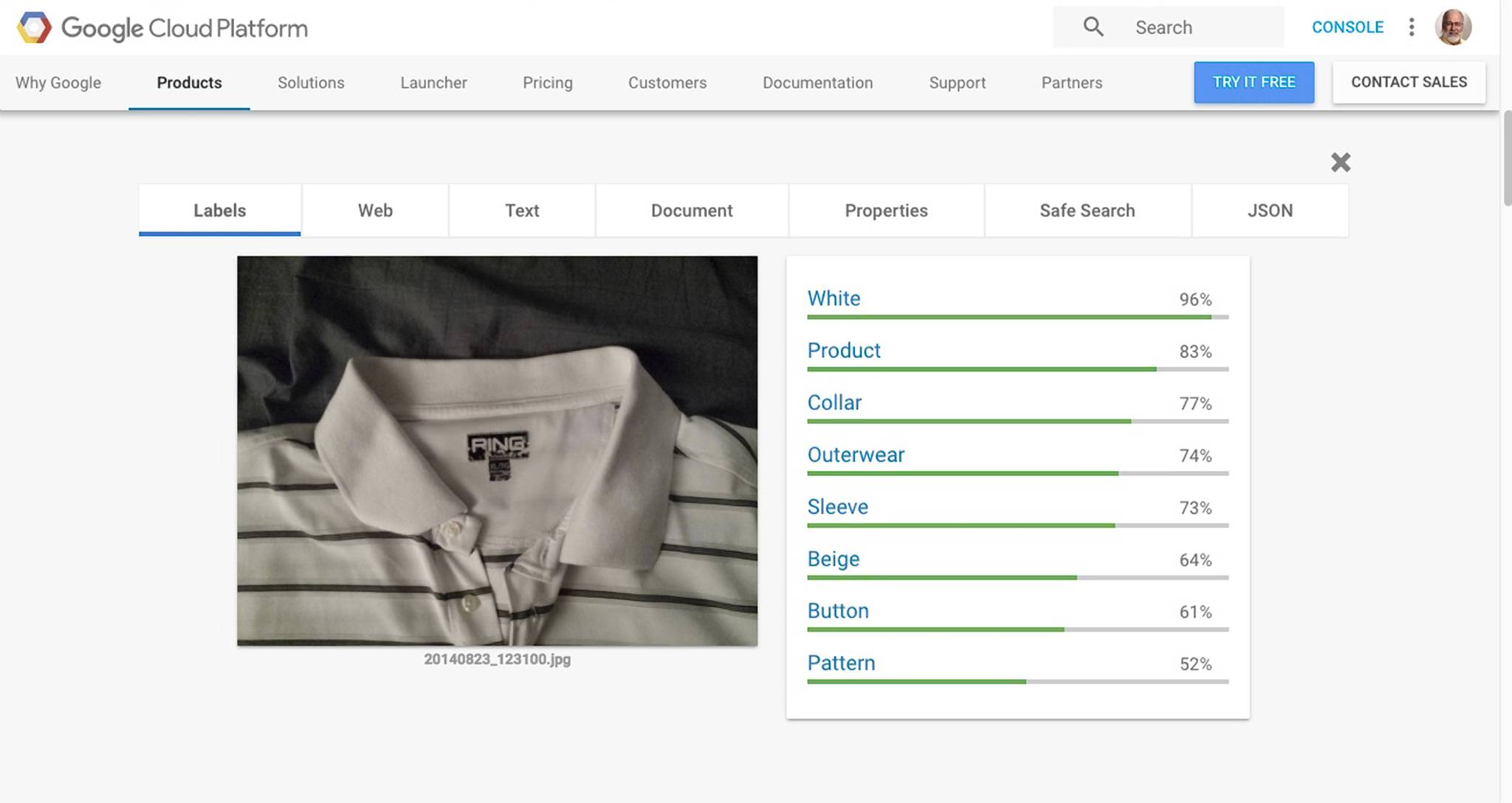

Google Vision

Next stop on my tour was Google Cloud Vision. Much better. “Collar” was good, and maybe even significant. But still. Big picture, it’s a shirt.

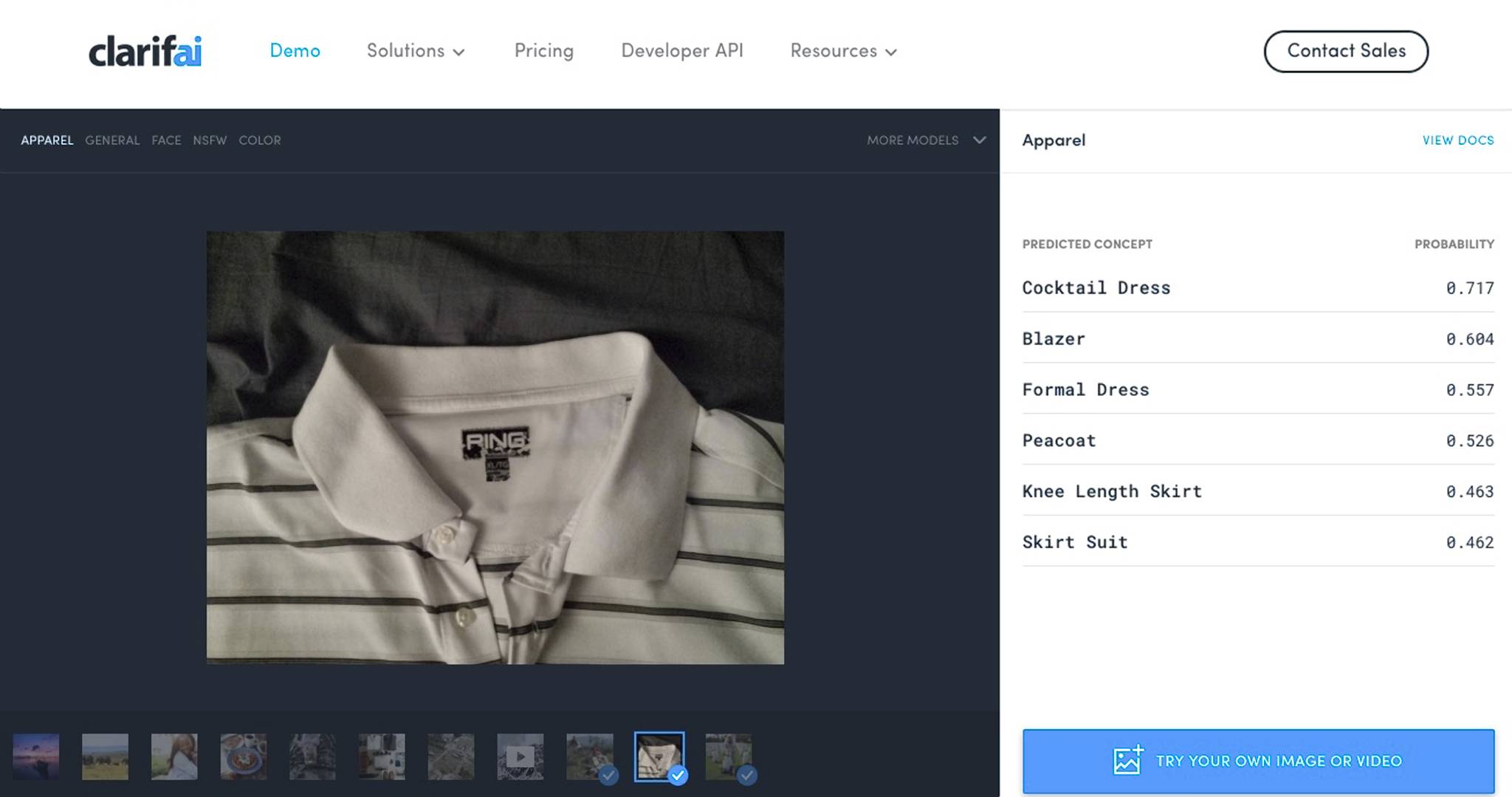

ClarifAI

ClarifAI was pretty sure the picture had something to do with clothing. But its guesses were pretty darn lame. Cocktail dress? Blazer? Peacoat?

Rekognition

At Amazon Web Service’s Rekognition demo, the shirt just didn’t ring a bell.

Play ball!

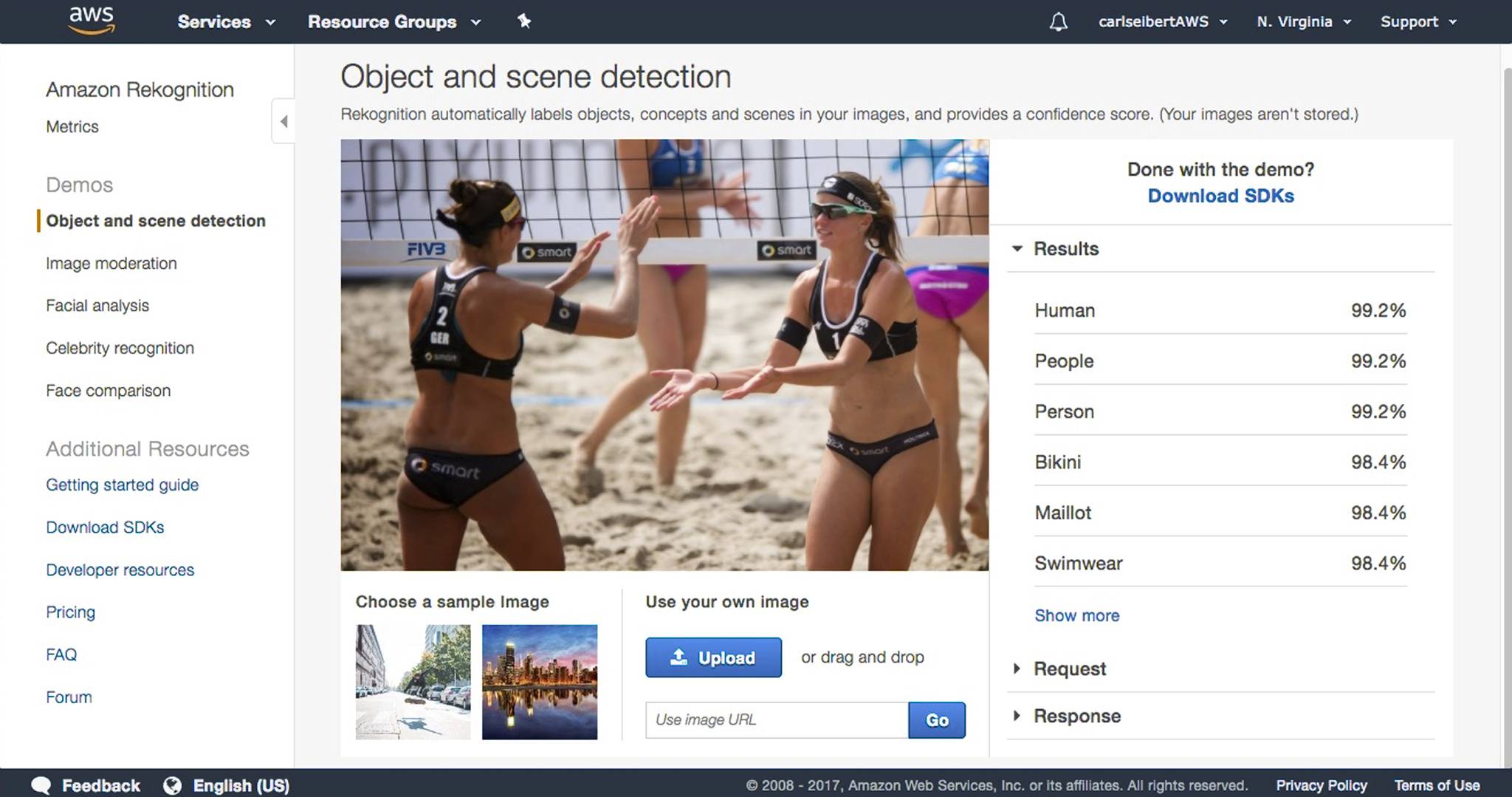

Next up, CloudSight, with a new picture (with a nod to the “brassiere” silliness).

This picture is a practical exercise. Tens of thousands of pictures like this live in the archives of sports publications, agencies and photographers worldwide. It’s a “jubo” (short for “jubilation”), or reaction photo. Such pictures are stock-in-trade for thousands of sports photographers and editors. These pictures depict a sport, but not the game action of that sport. As a sports picture editor, I published hundreds of them, reporting on many different sports, including beach volleyball.

The big question here is, “Since there’s no ball in the photo, will any of these services be able to tell that this is volleyball?” Or, for that matter, will they give us keywords that the owner or would-be buyer of such a picture might actually search for to find the photo?

Not at CloudSight. Apparently, the people who teach these systems are just obsessed with clothing! I’ll admit, “Sports bra” is a pretty good catch. The tops of women’s beach volleyball uniforms are in fact sports tops. But I can’t think of any context where the owner of such a picture would look for it as “sports bra”, or “top”, or whatever. This is a sport, not a fashion show. Focus, people! Er…Focus, machines!

Rekognition

At Amazon’s Rekognition, we are told that these are “human” “people” who are “persons”. (Bold guess!) Also, that they are wearing “bikinis” (close enough), which are “swimwear” and “maillots”. Now, a “maillot” is a one-piece swimsuit, the opposite of a bikini. Anybody who has ever taken a multiple choice test knows that antonyms aren’t likely to both be right. And what’s with the clothing thing?

Flickr

At Flickr, “sand” and “people”. Weak, but it was the first system to understand that we are on a beach.

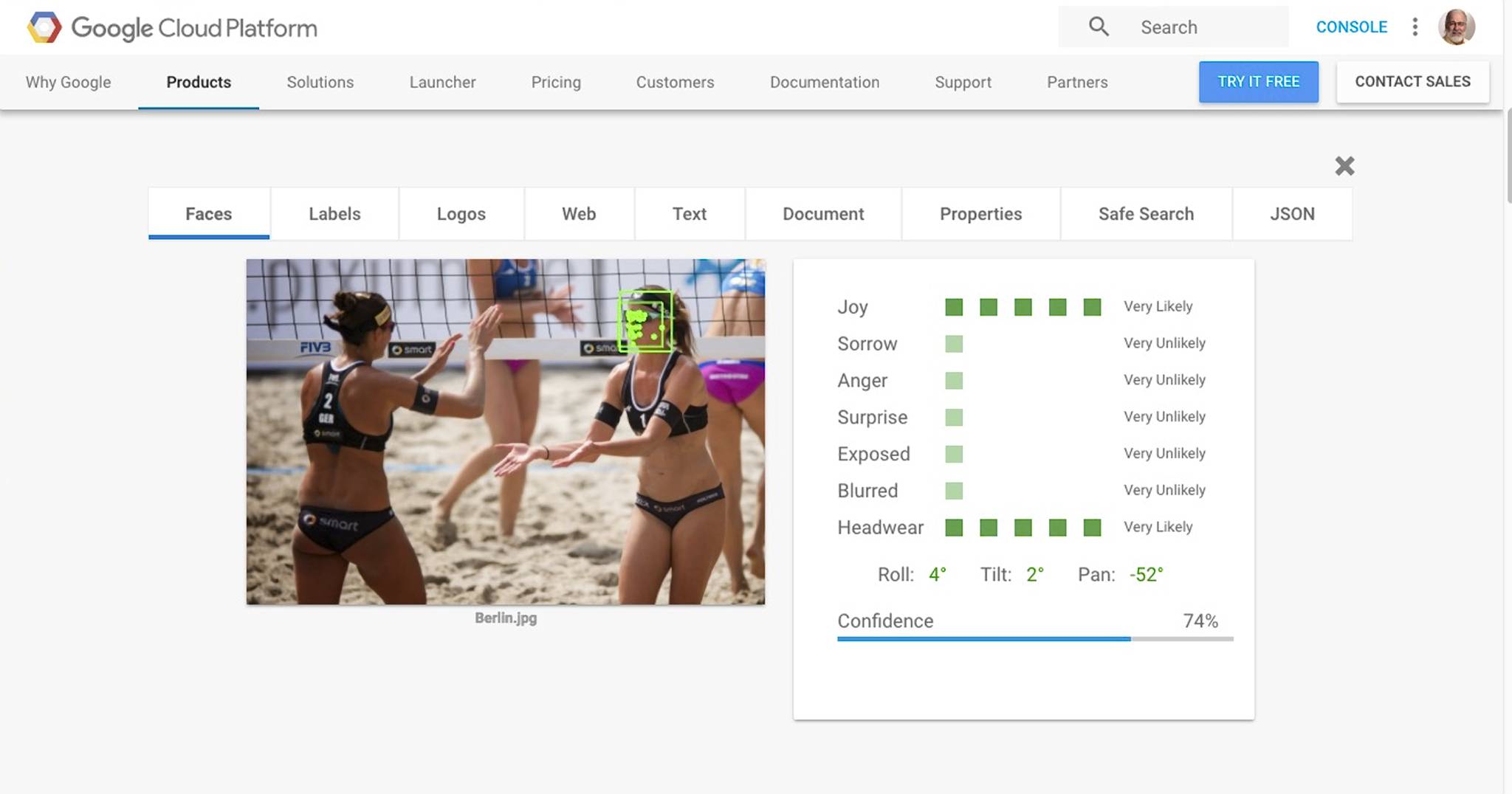

Google Vision

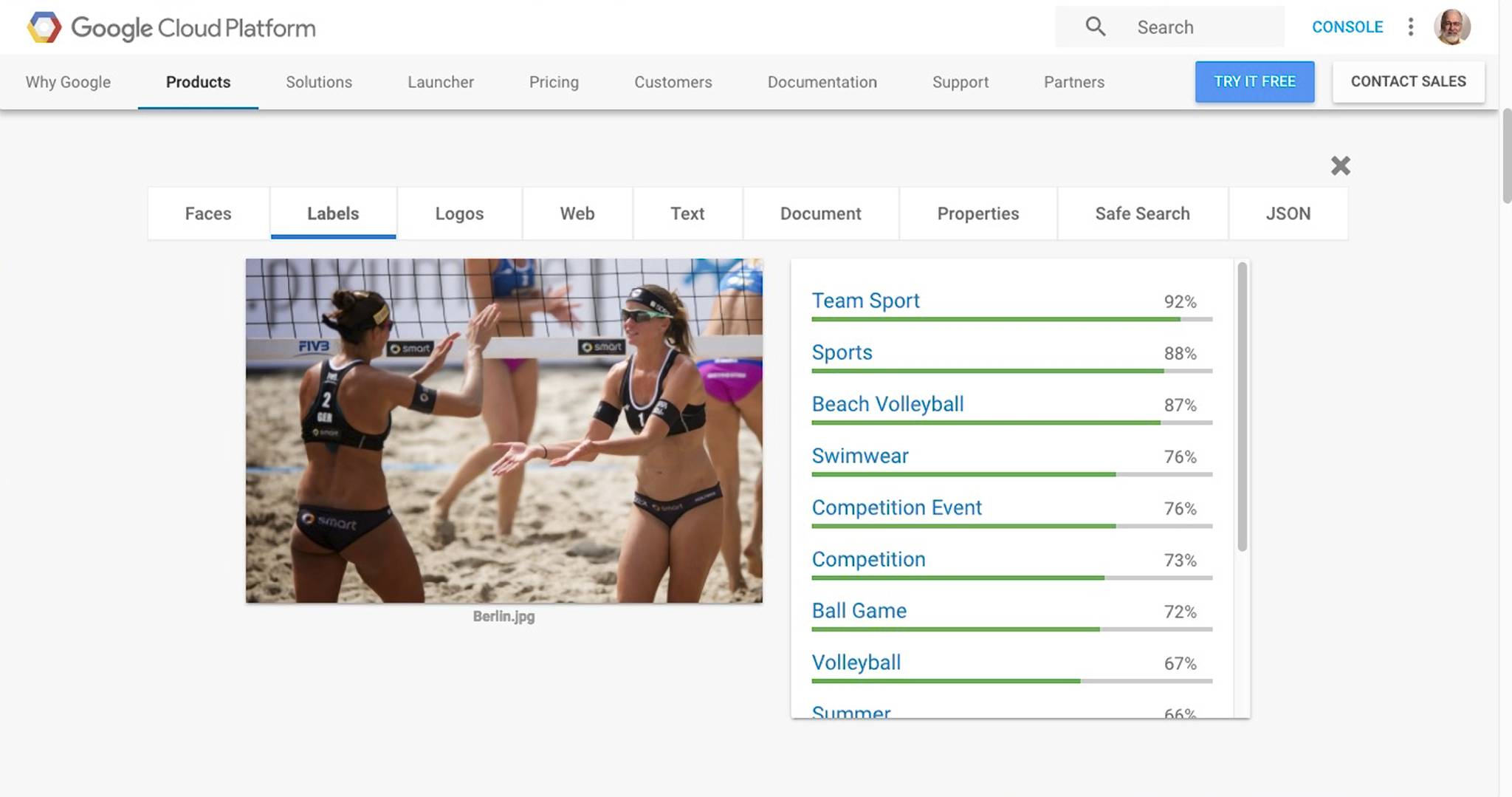

At Google Vision, where the biggest of big data lives, we have a “team sport” that just happens to be “beach volleyball”. Yup. It’s a “competition”, a “ball game”, it’s “summer”, and it’s even “ball over net games”. Check and check. And yes, the players are wearing “swimwear”, more or less. The player facing the camera is joyful and wearing headwear. All true. Woo hoo! Google Vision also grabbed the text “Smart” from the logo.

Google Vision looks like our winner for this image. It came up with keywords that are correct, and it appears to have some grasp on the meaning of the picture.

(Did you notice that none of the machines noticed the players were women? Am I the only one to see that?)

But are these results useful?

We have to consider use cases.

But first, no matter what we might intend to use this picture for, we need to consider that we need a caption. Who are these players? Have they just won a point, a game, or the championship? What tournament are we seeing? Where is it being played? At what point in the tournament did this happen? Those are all caption questions, which will likely require human answers. And once answered, they obviate the need for a bunch of keywords, artificially generated or otherwise.

In context

Then we have to consider the context of the collection in which the photo lives. It might (probably does) live in the archive of the tournament promoter, or the sport’s governing body. In that case, the insight that this is volleyball narrows matters down to exactly all the photos in the whole collection.

If this picture were to belong a news agency, or a sports photo agency, though, “volleyball” would be a meaningful part of its taxonomy. In this context, good keywords might be: “volleyball”, “beach”, “women’s”, “jubilation”, “name-of-tournament-or-tour”, and some other pertinent stuff that might not be in the caption. Google got a couple of those. We’ll need a little more before we see a jubo picture of archivists high-fiving.

Maybe the picture belongs to the company that makes the uniforms. In this context, yes, knowing that it’s a volleyball picture is useful. But truly useful keywords would define categories within the product line, or styles or colors, or maybe even specific SKU numbers. (In addition to all the information that’s found in a good caption.) Google’s results might help a little, but for what he or she really needs, the archivist at such a company would be on their own.

In my collection, what’s significant is the Smart car company brand name. (I drive a Smart.) So for me, good keywords would be: “Smart”, “beach volleyball” and “hot-looking women”. Only one of which was returned by one of the AI systems we tried.

(I didn’t shoot this photo, by the way. It was sent to me because of the Smart connection. There was no metadata on the file at all, so its story is uncertain. By reverse image search, I was able to determine the venue, the series of the tournament, and make a good guess at who the players are. I can guess from how it was used on the web that it was probably a handout picture provided by the tour organizers. I have no clue who shot it. It’s a poster child for why all pictures should have metadata and why all website should preserve metadata.)

Job security

So there it is. Cognitive image recognition and auto-tagging are all the buzz right now. Someday, the technology will help us mark up our content and search in fabulous new ways. But not yet.

In the near future, there’s not much worry (or hope) that machines will take part of our jobs away.

* (Keywording isn’t as easy as it looks, by the way. One of many pitfalls is that we assign different keywords as we learn more about the collection, and we just “drift” over time. Which is one of the reasons I advise, dear readers, that you use captions, written in natural language, as the primary descriptors of your images. In keywording, the concept of controlled vocabularies attempts to address fight the drift. Automation will someday – soon, hopefully – also help. I promise I will do a series of posts about keywording soon-ish)

Do you have an artificial intelligence tale to tell? Have you found a niche where image recognition is providing practical benefits? Prove to the Captcha you’re a human and dive into the comments!

Very enlightening.